‘Active’ versus the ‘redundant lives’ of things[1]

Paintings and prints of the early modern period serve to document the development of domestic culture over an epoch of profound economic, social and cultural change and place historical or archaeological objects in a specific functional or symbolic context that is normally absent from the excavated record. The archaeological deposit, whether a rubbish pit or latrine shaft, post-hole or a midden, normally reflects the final point of discard or loss of a possession or utensil. Only strict ‘time capsule’ deposits, such as a violent destruction horizon or a shipwreck, for instance, can reveal something of the ‘active life’ of an object prior to deposition.[2] The image, particularly those depicting the domestic interior, offer a glimpse of objects in use before discard and crucially in their relationship to the building, its interior design and spatial configuration, and in relationship to other objects, which may or may not be functionally related. In addition, these sources also connect objects to people and place the artefact in a contemporaneous social and ideological matrix, which on discard is frequently ruptured. The issue has been defined as the ‘equifinality’ of archaeological evidence, where the recoverable material culture can only remain a sample of past reality.[3]

As in the case of the documentary records, the study of historic objects in contemporary pictorial representations is not without its risks and pitfalls. Where perhaps until the early 20th century it might have been assumed that the paintings of, say, the Dutch Golden Age were to some extent representations of everyday life, today we acknowledge a multilayered understanding of their function as contemporary depictions, which were informed by a wide variety of cultural, social and moral motivations. Erwin Panofsky (1892–1968) was the first to interpret Jan van Eyck’s Anolfini Portrait (1434) not only a depiction of a wedding ceremony, but also a visual contract testifying to the act of marriage. Panofsky identifies a plethora of hidden symbols that all point to the sacrament of marriage. In his various iconological studies he identified at least three strata of meaning: primary of natural subject matter, secondary or conventional subject matter and tertiary or intrinsic meaning or content (iconology). In recent years, this approach has been refined particularly in respect of Netherlandish art by Eddy de Jongh and others, but Panofsky’s ‘’disguised’ symbolism is still very much influential in the study and understanding of northern European historic art.[4] The pictorial record of the transition to modernity acts as a window on the age, its materiality and its mentality; it holds a record not only of the multiplicity of things but also, essentially, a multiplicity of behaviours and thought, both of which determine quotidianity.[5]

In recognizing the value of contemporary iconographic sources for hermeneutics research in historical archaeology, it is important not to underestimate the importance of graphical evidence for empirical study, whether it be for dating or principally to help identify the active lives of historical artefacts. Our understanding of the use of silver-gilt and base metal dress hooks in 15th to 16th-century dress, which have become such a staple feature of the Portable Antiquities Scheme annual reports for England and Wales, would have been compromised without the series of portrait drawings by Hans Holbein the Younger of Henrician court figures and other secular studies, which show how they were used to close dress in the age before the button became ubiquitous.[6]

Pre- and post-Reformation art in the Netherlands and Germany

Late medieval panel painting commissioned for private devotion, particularly those that set the Lives of the Holy Family and those of the Saints in the contemporary domestic realm, reveal an increasing emphasis on material comfort illustrated by a wide range of utensils and rich furnishings. Robert Campin’s Annunciation triptych of c.1427–32 contains a wealth of domestic detail. Patrons (they are present here peeping through the ajar door of the chamber) were concerned to record as much of the paraphernalia of their own lives as a strategy to place the Saints into their own world and to participate in the sacred drama. The Annunciation by Petrus Christus of 1453[7] achieves a similar impact by foregrounding a contemporary utilitarian Rearen stoneware bottle to hold the sacred flowers of the Virgin. As Keith Moxey has previously noted, we are not dealing with ‘reality’ in these scenes, but rather a ‘reality effect’, which may be described as an ‘illusionist strategy of late medieval artists to represent the deployment of a visual rhetoric intended to make the Christian story both relevant and accessible to the majority of Christian believers…The miraculous powers ascribed to certain of these images depended upon a religious imagination that had been trained to infuse the natural with the supernatural’.[8] The key to an archaeological appreciation of these sources is the recognition of the religious and social motivations of the depicted domestic ‘reality’.

This ‘bourgeois realism’ of Netherlandish and German art of the 15th to 16th centuries forms a rich vein for comparative historical study. The linen-draped table illustrated in Dieric Bouts’s Christ in the House of the Pharisee Simon of 1460 supports a selection of archaeologically-attested dining and drinking ware of the period, including Siegburg stoneware drinking jugs, glass beakers, table knives and pewter flatware, together with tableware that does not normally survive in the archaeological record, such as wooden trenchers.[9] The pictorial source is an essential iconographic reference for reconstructing the functional and social relationships of the various tableware media employed in burgher households of the period. Reconstruction of North German ‘Hanseatic ‘Wohnkultur’ depends on both the quantitative archaeological record of stoneware frequencies and a comparative-qualitative analysis of contemporaneous iconographic images that records the non-archaeological or ‘missing artefacts’.

1a. Holy Family at a Meal of c.1495-1500 by Jakob Jansz and 1b. Joseph explaining the Dreams of the Baker and the Cupbearer of c.1500 by Jan Mostaert (reproduced by permission of Wallraf-Richartz Museum (Repro: Rheinishes Bildarchiv Köln and Mauritshiuis, The Hague, respectively)).

The Haarlem painters Jakob Jansz in his depiction of the Holy Family at a Meal of c.1495–1500[10] (Fig. 1a) and Jan Mostaert in his Joseph explaining the Dreams of the Baker and the Cupbearer of c.1500[11] (Fig. 1b) set the scriptural drama firmly in the contemporary domestic setting of the urban mercantile households of the North Netherlands. In both the white linen-draped table is central to the action. Siegburg stoneware drinking vessels share the table with wooden and pewter flatware. In the Joseph narrative the main character holds an ornate pewter wine flagon. With their detailed representations of merchant house interiors and the precise and relative location of domestic utensils within the space, these images are amongst the most evocative visual documents of dining culture amongst the emerging middle classes of the period, in which we see a range of media of differing value sharing a social interaction. The ‘reality effect’ of these scenes is of profound significance to the social archaeology of North West European merchant communities, enabling a reconstruction of ‘Lebenswelt’ through the cross examination of the synchronous material and visual documentary records.

2. Last Supper by Mechtelt toe Boecop, 1576 (reproduced by permission of Stedelijk Museum, Kampen).

The dressed and laid table is a central feature of Netherlandish religious art through into the 17th century and a continuing rich source of economic, social and cultural information on domestic objects for the historical archaeologist. The Utrecht painter Mechtelt toe Boecop’s Last Supper of 1576 is an example of the Renaissance influence on the genre (Fig. 2).[12] Here we observe a mounted Cologne-Frechen style Bartmann jug being used as a drinking jug on the table and a mounted Cologne-style Bartmann pitcher being used as a wine or water decanter placed below the table. Once again the Rhenish stoneware, which has a ubiquitous archaeological distribution,[13] is depicted in a ‘live’ situation alongside the clear Venetian-style glass beaker, pewter ware, table knives, spoons and treen on a bleached white table cloth, all of which are missing or at best rare in the excavated record. The visual snapshot of the ‘active life’ of an archaeological object is of great interest despite the illusionary historical reality of a biblical event.

Low Countries painting of the 16th century comprises a series of religious, mythical and secular themes set in the domestic sphere that feature well-attested archaeological objects prominently and create a rich functional and social matrix for the study of everyday ritual (‘Wohnkultur’). Marten van Heemskerck’s portrait of the Haarlem patrician family of Pieter Jan Foppeszoon of 1530 is among the earliest representations of a wealthy merchant family.[14] The seating around a dressed and laid table emphasizes the centrality of table culture in defining the ideal of the early modern family. In addition to the exotic foods, the pewter flagon, glassware and silver chalice sets the social bar for this generation of burgher family art. Pieter Aertsen’s Christ in the House of Martha and Mary of 1553[15] and Jan Beuckelaer’s Four Elements of 1570[16] are set in the kitchens of urban merchant houses and illustrate a wide range of contemporary kitchen and table ceramics, glass and metalware scattered around the floors, on tables and suspended from the walls. These narrative scenes are highly theatrical representations of domestic reality but it is worth pausing to observe the relative locational relationships within the various spaces. It is notable that the red earthenware cooking ware is usually depicted on the floor and that the mounted stoneware, glassware and, in the case of the Aertsen, the Antwerp maiolica vase, are placed on the tables and is prominent positions. As in the late Middle Ages, the artist’s objective was to attempt to involve the patron and viewer in the action, the semblance of reality amplified by the depiction of real objects chosen to fulfill a precise function and social role.

Images expressing overt satire are not without interest for the archaeologist. An engraving of around 1540–6 depicting drunken Bacchus Singers after Hieronymous Bosch at a feast is a moral critique of indulgent excess.[17] The mock ‘playing’ of a glass flute and stoneware pitcher placed on the table represents the breaking of taboos in manners. Thus the deliberate misuse of real objects in a domestic ritual situation for social satire provides a further insight into the popular perceptions of those objects in early modern society. Pieter Breughel’s well known Peasant Wedding of 1568 is a further case in point.[18] The baskets of unmounted stoneware pitchers and drinking jugs emphasise the social milieu being satirized by the artist. To amplify the effect and the critique of excess, the stoneware vessels are foregrounded and depicted at a slightly enhanced scale. The illusionist purpose of the scene is of particular hermeneutic value to the social archaeologist dealing with commonplace archaeological objects.

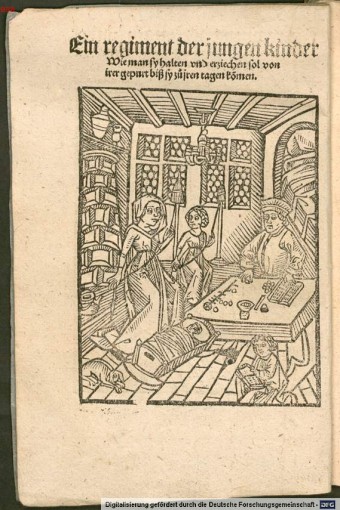

3. Häusliche Erziehung, woodcut by Johan Bäumler, Augsburg, 1476, reprinted here in the Kinderbüchlein of Bartholomäus Metlinger by Johann Schaur, Augsburg, 1500 (reproduced by permission of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Incunabula Catalogue, M-360,1,A1a).

Late medieval woodcut technology fulfilled a number of purposes, including the demand for cheap pedagogic visual propaganda for the emergent urban burgher class. The scenes from Häusliche Erziehung (‘Domestic Instruction’), printed by Johan Bäumler in Augsburg in 1476, and reprinted in the Kinderbüchlein of Bartholomäus Metlinger (printed by Johann Schaur, Augburg, in 1500) are typical of the genre (Fig. 3),[19] and in this scene showing the merchant and his industrious family we can observe the idealised ‘Ordnung’ of space and furnishings, fixtures and fittings, including beds, chairs, cradles, shelving chests, candelabra, hand-washing equipment, ceramics, glazing, even pets(!), and notably, the introduction of new technologies such as smokeless central heating (ceramic tile stove). Behind the idealised reality of the image, the relationships between the individual objects and between the people and objects enable us to help locate archaeological artefacts in the spatial and functional matrix of the historic household. Given the rarity of finding a tile-stove in situ in an urban building, such contemporary images are key to establishing the social and cultural milieu in which these objects were circulating and also to understanding their importance in the living space and how they functioned (i.e. set against a wall through which the stove was serviced and expelled its fumes). The ceramic tile-stove continued to be depicted as a centerpiece of social aspiration and domestic harmony in European burgher culture throughout the 16th century, as we can observe in an engraving representing January in a Months of the Year cycle by H.S. Beham of 1520 showing a wealthy patrician dining scene.[20]

Paintings of the Dutch ’Golden Age’

Oil painting of the Dutch Golden Age, particularly works depicting the domestic interior and still life compositions, appears at first glance a compelling source of social and cultural information for archaeologists and all those studying the emerging materiality and mentalities of early modernity. After all, this is a truly vast documentary resource. On the basis of statistical analyses of inventories and the number of painters active in Holland, economic historians have calculated that Dutch painters produced over 5 million pictures of all genres during the 17th century.[21] Around 1640, about two thirds of the population of delft lived in homes with paintings, with an average of eleven works per household. Overall, most numerous were landscapes, followed by portraits and history paintings, but interiors and still-lifes made up close to 10 per cent, or about half a million works, mainly oil on canvas. These were aimed at the broad spectrum of middle class buying power. These paintings were not produced on commission but speculatively in the main, in the hope that customers would desire them. It is agreed that Dutch genre paintings are likely to have fostered demand for the modes of living and goods they presented in such radiant fashion.[22] This output was created and consumed by a society that saw dramatic advancements in its material circumstances during the 17th-century. Until the late 18th century the Dutch Republic enjoyed the highest standard of living in Europe; wages were higher and inflation non-existent. Not surprisingly homes were filled by a vast range of fashionable and luxurious commodities, many reflecting overseas commercial contact.[23] Pieter de Hooch’s Interior with Women beside a linen chest of 1663[24] and Cornelis de Mann’s Family at a Dinner table of 1665–70[25] depict the new domestic luxuries of the mid-century – the ebony-inlaid linen press (replacing the chest), the starched white table napery (replacing the spittoon and the hand) and garnitures of white faience and silverware are emblematic of the new wealth of the nation and forewarning of excess.

The ideal of home and conceptions of the early modern nuclear family in its intimacy, domestic comfort and luxury amongst the north-west European urban middle classes can be seen to crystallize in 17-century Dutch genre art. Crucially, the illusionist effect is amplified by the presence of people in the scenes, and where there are no people, such as in the still-life, the scene is clearly habitable. The interaction between space, object and person is key to our archaeological interest in reconstructing these functional and symbolic relationships. The contextual opportunities offered by the depictions of the domestic interior for the socio-economic investigation of synchronous excavated assemblages are as significant as the historic probate inventory or testament.

The 17th-century Dutch home was both a private place and the showcase for the family’s values, status, wealth and taste. The choice of pictures on the wall was an important way for the household to project its self-image while affirming its investment in the values of the wider community. Scenes of daily life placed the home and family on display as ‘a way of imagining, reinforcing and crafting an ideal of domestic order and virtue.[26] The naturalistic genre gave this community a virtual mirror image of itself, but we recognize that the highly idealised and selective reflection it saw was perhaps more about the way it aspired to be than the way it really was.

4. The Account Book by Jan Steen, c.1660-63 (collection of T.C. Heywood-Lonsdale (reproduced by permission of The Hunterian, University of Glasgow).

Thus Dutch genre scenes of the 17th century were not intended as mimetic representations of social reality. They were in part aspirational visions of the successful burgher lifestyle and part exercise in moral edification, employing a figurative language that everyone would have recognised. Although not a directly relevant painting for detailed archaeological cross-analysis, the Account Book, by Jan Steen of the early 1660s in The Hunterian, University of Glasgow,[27] provides a case-study in the depiction and arrangement of people and domestic objects for the purpose of moral instruction (Fig. 4). The woman seated to the right outside a tavern is a one of Steen’s dissolute women, if not a prostitute. The old lady in the middle is a procuress and the lady in the headscarf to the left is a tradeswoman who has come to present her pofboek and remind her customer of her debt. The woman is just ahead of the procession of townspeople who are about to expose her scandalous state. The harbour is a reminder of the brothel’s best source of customers. The various objects in the scene all help to condemn the prostitute: her blouse is undone, an indication of low morals (and she is not breast-feeding her son!); the spinning wheel, a symbol of good housekeeping, is neglected; as is the child who is too large for its kinderstoel (he is spoilt, having three dolls and his tin feeding bottle has fallen neglected to the ground); the bird cage is an allusion to intercourse and to a libidinous lifestyle – Vogelen in Dutch is to fornicate – (its position within the image makes it a sign for the brothel); the vine is a symbol of the consumption of alcohol and of associated lewd behaviour; the rose in the pot behind the prostitute is the flower of Venus and the thorns a reminder of the dangers involved; the bucket would have been used to bring back goods from the market, but lies empty because the prostitute’s credit has run out; and the gourd on the belt of the tradeswoman is the symbol of brevity (as a proverbially fast-growing plant it symbolised the rapid flowering and passage of feminine beauty). One can decode the domestic mayhem of Jan Steen’s various depictions of the Dissolute Household (1663–65) or In Luxury Beware (1663) along similar lines.[28] Steen was renowned deliberately inverting the appropriate familial behavior of scenes by Pieter de Hooch and others by minutely cataloging the effects of intemperance as they reverberate through the household. The reckless abuse of luxury Delftware dishes, pewter plates and jugs and glassware tipping from the table or lying on the floor amplify the didactic effect of this study in the transgression of the social utility of fine table wares.

5. The Idle Servant by Nicholaes Maes of 1655 (reproduced by permission of the National Gallery, London.)

Many Dutch genre painters treated the domestic interior as a world of women, children and maids.[29] In Dutch society fathers may have ruled but they are often strikingly absent from scenes of domestic life. Nicolaes Maes created a number of ‘female interiors’ with mothers with children and maids at their chores in the 1650s. While The Lacemaker [30] appears to record an authentic scene of quotidian domesticity, with the child’s delft porringer on the floor alongside its overturned pewter feeding bottle and the (antique) Siegburg stoneware wine jug placed strategically out of reach on the adjacent table, Maes’s depiction of maids and their mistresses is altogether more critical. In the Idle Servant of 1655 we see a sleeping maid with hand to chin, and her mistress suggesting she is not worn out from work but has succumbed to sloth or idleness, the state of female melancholics caused by lovesickness (Fig. 5).[31] Maes capitalised on the widespread belief that maidservants were lazy and lascivious, prone to petty thievery and a threat to the stable household.[32] For the archaeologist, there is significant interest in the mixed assemblage of base metal and lead-glazed red earthenware cooking and food preparation vessels together with the delft plates and dishes scattered over the floor awaiting washing up or replacing on shelves. Note also the stacked blue-and-white Wan-Li-style delft dishes on the dresser. The mistress of the household is reduced to carrying the Westerwald stoneware decanter to the dining table herself! Notwithstanding the morality tale allegorised by this scene, the synchronology of the depicted kitchen and tableware provides a documented historical fix on the functional and social interrelationships of these recognisable archaeological objects whose excavated context is more likely to reflect the process of discard rather than use, or rather here misuse.

6. Lady Drinking with a Letter of 1665 by Gerard ter Borch (reproduced by permission of the Sinerbrychoff Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki).

As in the case of late medieval devotional art, the depiction of contemporaneous popular domestic products, such a Rhenish stoneware or Dutch delftware, in intimate genre scenes of the 17th century, serves to cement the illusion of real time and space, together with social milieu and the moral message. Cobalt-painted Westerwald stoneware jugs and tankards are ubiquitous irrespective of the social setting and symbolic purpose of the subject. In Gerard ter Borch’s Lady Drinking with a Letter of 1665 we see a fine Westerwald wine decanter on a table alongside a Turkey carpet (Fig. 6).[33] The Lady drinks from a crystal glass and is dressed in fine silk; whereas In Nicolaes Maes’s Old Woman Praying of 1655–58 the old woman’s utilitarian dress, the mix of earthenware pipkin, Westerwald stoneware tankard, and meal of gruel, cheese and fish radiate pious frugality.[34] It is their precise depiction and positioning within the social and ideological matrix of these imagined domestic scenes that we gain an insight into the ‘active lives’ of these archaeologically familiar Rhenish stoneware vessels.

Still lifes of domestic commodities and foodstuffs are another key strand within the genre of 17th-century Dutch secular painting and a mechanism for reflecting the purchasing power, social aspirations and moral concerns of the community.[35] In addition, the technological and commercial pulses of the Dutch Golden Age and its consumer excess are emphasised: the exotic fruits, wines, spices, and later coffee and tea; the Venetian glassware; seashells from the Indian Ocean; porcelain from China and tobacco from America – all contribute to an unprecedented impression of luxury and novelty in the domestic sphere created by the Dutch lead in the new global economy. Many ‘sumptuous still lifes’ (Pronk-stilleven) were commissioned explicitly to show off (‘pronken’), one’s purchasing power. In Osias Beert’s Still Life with Cherries and Strawberries of 1608[36] we observe the social impact of the first Amsterdam auctions of Chinese porcelain in 1602 and 1604. It is significant that at the start of the century we see exotic Chinese ‘Kraak’ porcelain being combined with luxury precious metal and Mediterranean crystal glassware. The relevant regional archaeological sequence for the period, such as that documented at the town of Duisburg on the confluence of the Rhine and Ruhr, reveals the relatively exclusive social distribution of the early imported Chinese porcelains in the community during the early 17th century, with several large dishes being excavated on the sites of patrician houses.[37] The sequence also records the immediate impact of these exotic imports on regional ceramic manufacture. A new range of imitative products were made in Netherlands tin-glazed earthenware local utilitarian red earthenware potters in the Lower Rhineland were stimulated into inventing slipware for the table. But during the course of the 17th century, with the accelerated importation of Chinese porcelain by the shipload, the social value matrix of this commodity may have changed yet again. In Jan Jansz Treck’s Still Life of 1649,[38] the Chinese blue-and-white porcelain bowl is part of a mixed table group containing pewter and a ‘forest glass’ beer flute. Archaeologically, however, Chinese blue-and white porcelain remains relatively elusive in the North-West European excavation record until the end of the century and it possible that the iconographic representations reflect an idealisation of the domestic table setting in the burgher household.[39]

General developments in consumer taste in the domestic sphere can be documented through Dutch genre painting over the course of the 17th century and it is possible to identify fashion trends in a number of key material categories. One candidate for future calibration of iconographic and archaeological data is tin-glazed earthenware, which occurs abundantly in both records. The trend in this sector towards plain white wares from the middle of the 17th century onwards can be traced archaeologically as in Duisburg[40] and in the home interiors of Pieter de Hooch, such as the Mother Nursing an Infant of 1658–60.[41] Here large lobed whiteware dishes are displayed prominently on the mantelpiece and it appears, given their importance, that in such orderly households they may have been be removed only on special occasions. Whitewares held a special place within Dutch society of the period. White was associated with purity and household cleanliness; hence the emphasis on starched white napery, white plaster walls and white tiles. It acted as a metaphorical antidote to polychromy and excessive ornament, which could be associated with profligacy and vanity.

The symbolic representation of modesty is a long standing theme in Dutch genre art and it is vital to recognize that on occasion the purchasing power of a particular household is being purposefully underplayed. Hendrick Sorgh’s 1663 portrait of the Bierens family is unusual for posing the family in the kitchen apparently engaged in some communal cooking.[42] Head of the house, Jacob Bierens, enters holding a fish, but he was no fisherman and would not have been in charge of the shopping. But for this Mennonite family, the Lenten food must have ciphered frugality and everyone is participating diligently, while the eldest son is providing musical accompaniment to emphasize the harmony of family life. It is quire deliberate, therefore, that no exotic or elaborately decorative household goods are depicted. Notwithstanding all the metaphorical grammar of this scene, it is a rich source of information on kitchen operations in a merchant home of the period, and contains important detail on food preparation and washing up procedures. One detail is of particular contextual resonance to he historical archaeologist. A row of blue-and-grey Westerwald stoneware panel-jugs hangs on pegs in the background above the sink, ready for use, as they do above the old lady spinning in the painting of the same name by Nicholaes Maes’s (1650–60).[43] The neatly suspended jugs reflect order and tidiness, either in the bustling merchant household or in back-of-house light industrial setting. Westerwald jugs account for around 6 percent of all ceramics excavated on the Lower Rhineland urban sites during the second half of the century.[44] This practical and effective method of storage may help to explain why a relatively modest number of such highly decorated vessels may have entered the archaeological record.

7. Still-life with a Stoneware Jug of 1658 by Pieter van Anraadt (reproduced by permission of the Mauritshuis, The Hague).

We do not actually need historic paintings to inform us about the consumption of tobacco in early modern Europe. Notwithstanding the comprehensive archaeological picture, rarely can we observe the ritual of smoking in the excavated record. Pieter van Anraadt’s still-life ensemble of 1658 combines all the paraphernalia of the new recreational habit – the clay pipes, tobacco wrapper, red earthenware smoking pot together with the essential Westerwald stoneware beer jug and drinking glass (Fig. 7).[45] This is a scene of private contemplative consumption of the fruits of the Dutch trade to the New World and intended as a deliberate counterpoint to contemporary tavern scenes showing the abuse of such commodities and the negative effect of alcohol and nicotine on the social order.

Image and object: conflict and correspondence

The figurative art of the late medieval to early modern domestic interior in north western Europe represents a primary resource for the exploration of the economic, social, material and ideological changes in contemporary culture that define the emergence of Western modernity. Cross-referencing this rich visual record of change with the evidence of archaeological distributions of the domestic artefacts that populate and animate these scenes has the potential to create a powerful interpretative tool for investigating consumer habits and trends and aspects of social behaviour amongst groups in society that did most to create the world we now recognize as a modern one. The pictorial sources in question, from pre-Reformation devotional works to the sumptuous still-life paintings of the Dutch Golden Age were never intended as mimetic studies in social reality. They were in part aspirational visions of the lifestyle of the emerging urban mercantile elite, in part exercises in social engineering, and in part templates for religious and moral edification, each employing a symbolic visual grammar that the middle class owners of this art would have recognised. Domestic buildings, interiors and utilitarian objects operate within this complex matrix of motivations and enhance the crucial ‘reality effect’ for the viewer. We are conscious of the illusionist purpose of these works but, once decoded, we recognize their scope for interdisciplinary historical research into the materiality of the age of transition.

European historical archaeology involves reconciling material and documentary sources of evidence for the past, which escalates in its mass and complexity from the 15th century onwards. For the late Middle Ages and early modern period we have long recognised the importance of addressing the contemporaneous written record and are aware of the frequent correspondences and conflicts between artefact and text. The pictorial record offers a parallel investigative mechanism but poses many of the same challenges: it is partial and biased but it contains many of the disarticulated and decontextualised archaeological objects that concern us. Most significantly, and perhaps more explicitly than the text-based sources, it locates them in relation to spaces, people and to other objects. Artefacts help enforce the illusion of reality and play an emblematic role in the action.

Although we as archaeologists have long recognised the importance of the historic pictorial record, our methodologies and hermeneutic devices have not been deployed sufficiently to exploit this rich comparative resource for better understanding the use of objects, their interrelationships, and their position in the social, cultural and ideological matrix of historical society. As the paintings and prints show us, objects were of critical importance to delivering a social, religious or moral message. Even the most utilitarian of objects held symbolic power in the visual documentary world. The prospect of structured archaeological-art historical comparative research offers new opportunities for exploring the ‘Lebenswelt’ – the lifestyles and mentalities of the early modern household and community. This short survey can only hint at the possibilities offered by such a study. The need to pilot surveys of particular genres, artistic themes or the works of individual artists and to test some of our archaeological data and assumptions is as urgent now as it was ten or twenty years ago. If we don’t address this challenge at some defined point in the future we risk continuing to plough our own single disciplinary furrow and fail in our ambition to develop a true historical archaeology of the early modern domestic sphere. Worse still, much of our excavated material will remain orphaned and only of interest to other archaeologists.

Since 2010 Professor David Gaimster has been Director of The Hunterian, the University of Glasgow museum and gallery service following appointments as Assistant Keeper in the Department for Medieval and Later Antiquities, British Museum, London (1986-2001), Senior Policy Advisor for Cultural Property, Department for Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS), London (2002-04), and General Secretary and Chief Executive of Society of Antiquaries of London (2004-2010). Following a PhD in historical archaeology at University College London he has published extensively on late medieval to early modern European material culture and also on international cultural property policy issues. He is Docent in Historical Archaeology at the Department of Cultural Studies, University of Turku. He has organised several major exhibitions that have also toured overseas, including Pottery in the Making (Museum of Mankind, London, 1997) and Making History: Antiquaries in Britain1707-2007 (Royal Academy, London, 2007). His most recent book is Director’s Choice: The Hunterian, University of Glasgow (SCALA Publishers, London, 2012).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the following institutions for permission to reproduce illustrations:

The Wallrat-Richartz Museum Cologne; the Mauritshuis, The Hague; the Stedelijk Museum, Kampen; the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich; The Hunterian, University of Glasgow; the National Gallery, London; and the Sinerbrychoff Art Museum (Finnish National Gallery), Helsinki.

Notes

1. Since the presentation of this paper in October 2011 a version of it is now in press in the Journal for Post-Medieval Archaeology 46/2 (2012), 304–319, under the title: ‘The Geoff Egan Memorial Lecture 2011. Artefacts, art and artifice: reconsidering iconographic sources for archaeological objects in early modern Europe’.

2. Gaimster, David 1997. German Stoneware 1200-1900. Archaeology and Cultural History, London: British Museum, 131-133; Gaimster, David 2006. The Historical Archaeology of Pottery Supply and demand in the Lower Rhineland, AD 1400-1800, BAR International Series 1518, Oxford: Archaeopress, 144–145.

3. Verhaeghe, Frans 1998. Medieval and later social networks: the contribution of archaeology, in Die Vielfalt der Dinge. Neue Wege zur Analyse mittelalterlicher Sachkultur. Internationaler Kongress Krems an der Donau, 4. bis 7. Oktober 1994. Ed. by Helmut Hundsbichler, Gerhard. Jaritz and Thomas Kühtreiber. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Forschungen des Instituts für Realienkunde des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit. Diskussionen und Materialien, 3, 263–311.

4. Panofsky, Erwin 1972. Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York: Harper & Row, 5–9. For critique and further refinement of this approach see de Jongh, Eddy. 2000. The interpretation of still-life paintings: possibilities and limitations, in Questions of meaning. Theme and motif in Dutch seventeenth-centuiry painting, Ed. by Eddy de Jongh, Leiden: Primavera Pers, 129-148; and Bedaux, Jan Batiste 1990. The Reality of Symbols: Studies in the Iconology of Netherlandsh Art 1400-1800, The Hague.

5. Jaritz, Gerhard 1994. Methodological aspects of the history of everyday life in the late Middle Ages, Medium Aevum Quotidianum, 30, Krems, 22–27.

6. Gaimster, David – Parker, Karen – Hayward, Maria & Mitchell, David. 2002, Tudor silver-gilt dress-hooks: a new class of Treasure find in England, Antiquaries Journal 82, 157–196.

7. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (illustrated in Gaimster 1997, fig. 4.42).

8. Moxey, Keith 1996. Reading the “Reality Effect”, in Pictura Quasi Fictura. Die Rolle des Bildes in der Erforsching von Alltag und Sachkultur des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit. Ed. by Gerhard Jaritz. Forschungen des Instututs für Realienkunde des Mittlelalters und der frühen Neuzeit Diskussionen und Materialien 1, Vienna: Österrereichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 15–22; here see p. 8.

9. SMPK Gemäldegalerie Berlin, cat.533A (illustrated in Gaimster 1997, fig. 4.2).

10. Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne, WRM 471 (illustrated in Gaimster 1997, fig. 4.3).

11. Mauritshuis, The Hague.

12. Stedelijk Museum, Kampen, (illustrated in Gaimster 1997, fig. 4.18).

13. Gaimster 1997, 91–93.

14. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel.

15. Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam (illustrated in Pre-Industrial Utensils 1150-1800, Ed. by A.P.E Ruempol and A.G.A van Dongen, Rotterdam: Museum Boymans-van Beuningen 1991, 285).

16. E.g. Fire. Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Gent, inv.1986-AG (illustrated in Gaimster 1997, fig. 4.19).

17. British Museum P&D 1992,1–25,24 (illustrated in Gaimster 1997, fig. 4.26).

18. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (illustrated in Gaimster 1997, fig. 4.4).

19. Illustrated in H. Kunze, Geschichte der Buchillustrationen in Deutschland, Bildband, Leipzig (1975), pl.82; in The Illustrated Bartsch. Ed. by Walter L. Strauss. Vol.81: German Book Illustration before 1500 (part 2: anonymous artists 1476–1477). New York, 1981, 11; and also in Strauss 1968, fig. 8 (identified here as being printed by Benedikt Buchpinder, Munich 1488–9). The woodcut was reprinted in the Kinderbüchlein of Bartholomäus Metlinger, by Johann Schaur, Augburg, in 1500 (see Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Münchener Digitalisierungszentrum BSB-Ink: M-360).

20. Herzog-Anton-Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig. Illustrated in Strauss, Konrad 1968. Der Kachelofen in der graphischen Darstellung, Keramos 39 (1968), 22–38, fig. 12.

21. Sluijter, E.J. 2001. “All striving to adorne their houses with costly peeces”. Two case studies of paintings in wealthy houses, in Art and Home. Dutch Interiors of the Age of Rembrandt. Ed. by M. Westermann. Denver Art Museum and the Newark Museum, Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 103–128.

22. Westermann , M. 2001. “Costly and Curious, Full off pleasure and home contentment”. Making home in the Dutch Republic, in Art and Home. Dutch Interiors of the Age of Rembrandt. Ed. by M. Westermann. Denver Art Museum and the Newark Museum, Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 15–82.

23. Loughman John & Montias, John Michael. 2000. Public and Private Spaces. Works of Art in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Houses. Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, esp. Chapter I.

24. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 1663 (illustrated in Loughman, J. 2006, Between reality and artful fiction: the representation of the domestic interior in seventeenth-century Dutch art, in Imagined Interiors. Representing the Domestic Interior since the Renaissance. Ed. by Jeremy Aynsley and C. Grant. London: V&A Museum, 72–97, fig. 4.1).

25. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, (illustrated in Westermann 2001, fig. 38).

26. Chapman, H. Perry 2001. Home and the display of privacy, in Art and Home. Dutch Interiors of the Age of Rembrandt. Ed. by M. Westermann. Denver Art Museum and the Newark Museum, Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 129-153.

27. Priv. collection, on loan to The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

28. Dissolute Household: Victoria & Albert Museum, London WM.1541–1948 (illustrated in Loughman 2006, fig. 4.6) or Metropolitan Museum of Art, illustrated in Chapman, H. Perry – Kloek, Wouter Th. & Wheelock, Arthur K. Jr. 1996. Jan Steen. Painter and Storyteller, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, cat.21, fig.1); In Luxury Beware: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (illustrated in Chapman et al., 1996, cat. 21).

29. E.g. Frantis, Wane E. 1993. Paragons of Virtue. Women and Domesticity in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art, Cambridge: CUP.

30. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (illustrated in Westermann 2001, fig. 97).

31. National Gallery. London (Illustrated in Chapman 2001, fig.181).

32. Chapman 2001.

33. Sinerbrychoff Art Museum (Finnish National Gallery), Helsinki.

34. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (illustrated in Westermann 2001, fig. 102).

35. Berger Hochstrasse, J. 1999. Feasting the eye: painting and reality in the seventeenth-century ‘Bancketje’, in Still-Life Paintings from the Netherlands 1550-1720. Ed. By Alan Chong and Wouter Kloek. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and The Cleveland Museum of Art, Zwolle: Waanders Publishers

36. SMPK, Berlin (illustrated in Schneider, Norbert 1989. Stilleben. Realität und Symbolik der Dinge, Cologne: Taschen, 97).

37. Gaimster 2006, diagram 8d.

38. National Gallery, London.

39. Gaimster 2006, 98.

40. Gaimster 2006, diagram 8e.

41. Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. See Gaimster 2006, 96, for discussion of Duisburg Delft white tin-glazed earthenware sequence.

42. Netherlands Institute of Cultural Heritage (Illustrated in Westermann 2001 fig. 85).

43. Nicolaes Maes, De Spinster, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (SK-A-246, 1870)

44. Gaimster 2006, Diagram 5, p. 123.

45. Mauritshuis, The Hague, inv. 1045.