This article discusses the art-historical research of 20th- century textile art. Taking the process of my doctoral research as a case in point, I consider the ways in which research materials and sources influence the conceptions of textile art that are constructed in art-historical writing.[1] My research investigated Finnish textile art in the 1920s and 1930s. The historical context was the modernizing art system of a newly independent country. Textile art emerged as a separate field, as part of the professionalization of art and design.[2] Specialized training in textiles was launched in 1929 at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in Helsinki (est. 1871, now the Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture) where tuition focused on traditional hand weaving.[3]

Textile media were quite highly valued during the inter-war years in Finnish cultural life where the idealization of agrarian culture was part of the prevailing conservative politics of the country. Textile art was presented in this context as a gendered field of design.[4] Professionally educated textile artists, who were exclusively women in this period, displayed a public image of themselves as specialists in traditional hand weaving.[5] Modern textile art was lauded in exhibitions and magazines and there are many published sources from the period. Regarding textile material, I based my research mostly on the collections of Design Museum Helsinki (until 2002 the Museum of Applied Arts). The museum was founded by the Finnish Society of Crafts and Design in 1873 as the teaching collection of the Central School of Arts and Crafts. In the 1920s the museum was provided with its own premises and it launched regular exhibitions, staging among other events, exhibitions by leading textile artists, which also resulted in collection acquisitions. However, most of the material that I used in my research came to the museum later, as donations from individual artists or institutions, and what is more important, some of the items were not textiles at all.

Objects are at the centre of a wide range of studies, whether the particular interest is in the process of designing and making, the makers and manufacturers, the product itself, or how it is sold, used and perceived. But object-based research is an undertaking based on both limitations and assumptions. The most evident limitation is the lack of statistical validity. The destruction caused by time, pests, climate (especially pertinent to textiles) and disasters means the rates of survival do not indicate original volumes of production; on the contrary, the rare, beautiful or costly object has the greater chance of survival. If such value contributes to survival, it also prompts the use of objects in forms of different from that originally intended: the utilitarian can become a work of art (as have Amish quilts) and the exclusive, utilitarian (as often happened to second-hand fine cloths). This flexibility is the less obvious limitation of object-based research, for it means that an object’s value itself may change over the course of its history.[6]

In the quotation above the British textile historian Mary Schoeser highlights a central question of object-based research of history: what is the evidential value of the more or less accidental remnants that we are studying. Compared with the challenges of textile historical research in general, often studying anonymous objects with limited contextual information, my task should be easier. In my research, the “makers” or designers of textiles are known and they have lived relatively close to the present day. Moreover, textile artists in general belong to a group of professionals whose history is quite well recorded. However, I will argue that also a scholar of 20th-century textile art can face the challenge of limited materials.

In this article I reflect on the methods of selecting and managing the material for an empirical study in my doctoral thesis, trying to analyse some of the problematic encounters. My article questions the role of individual (unique) pieces of textile art and ask what other materials preserved in the museum collection can offer to art-historical research. Through my own professional history at Design Museum I knew the textile collections from personal experience.[7] At the beginning of my research process, I did not really know what I was looking for. I surveyed the archives and textiles from the inter-war period – or those, which I thought would date from that time, as most of the material that I used was not dated. While inspired by a variety of promising material offering ginzburgian ”threads and traces”[8], I acknowledged that the material that I was studying started to change my thinking about the whole concept of textile art. The scarcity of sources on the material production of textiles was the biggest challenge for my research. Some private archives donated by designers to Design Museum were crucial for the development of my idea of entrepreneurship. While providing many kinds of material to study, and not enough to understand what “really” was produced and when, they opened for me the possibility to read the story from traces.

Traces of entrepreneurship

1. Maija Kansanen: Wall hanging (DM G410), 1929, wool, linen and metal yarn (105 x 157 cm). The collections of Design Museum Helsinki (DM). Photo: DM / Rauno Träskelin.

Finnish textile art of the inter-war years has been appreciated for its high standard. The members of the new professional group were awarded international prizes and the colourful ryijys and modern tapestries of abstract pictorial quality and interesting texture are admired of their avant-garde aesthetic even today. One of the symbolic artworks of the period in the collections of Design Museum Helsinki is a wall-hanging by Maija Kansanen (1889–1957). (Fig. 1). The beautifully woven textile in distinct, Bauhausian style has been displayed in many exhibitions.[9] At least three unique decorative textiles like this “tapestry” (known in Finnish as kuvakudos) – to use the contemporary term – were bought for the museum collection directly from the artist who exhibited her works twice at the Museum of Applied Arts at the turn of the 1930s.[10] However, they represent only one side of her oeuvre. In fact, Kansanen ran a weaving studio in Helsinki, which also produced fashionable hand-woven utility textiles and fabrics.[11] Although we are accustomed to think that artworks are “woven by” the artist, the weaver of this “tapestry” was probably not Maija Kansanen herself, and this raises further questions about the nature of this art.

In her unpublished seminar lecture from 1988, textile artist Kristiina Hänninen listed enterprises headed by professionally educated textile artists in Helsinki from 1900 to 1940. Hänninen based her survey on advertisements and articles in design magazines.[12] Interested in the visibility of textile artists in the commercial context, I followed this route and found more traces of entrepreneurship, for example in the catalogues of the national fairs of trade and industry. Appearing alongside big companies and the textile industry, the names of contemporary textile artists represented their small textile studios.[13]

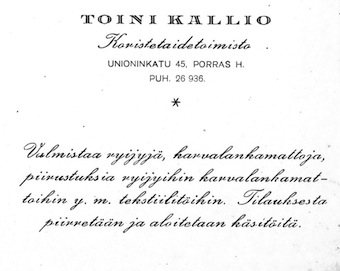

2. Calling card of Toini Kallio’s studio, “The Decorative Art Office” (in Finnish: Koristetaidetoimisto), 1930s. Toini Kallio archive, Design Museum Helsinki. Photo: Leena Svinhufvud.

My interest in textile artists’ activities was fanned by my findings in the museum. A small collection of textile designs, fabric samples and photographs by textile artist Toini Kallio (1891–1981), came to the museum in 1979.[14] Having previously worked for the Friends of Finnish Handicraft, Toini Kallio founded in 1923 her own studio, Koristetaidetoimisto, in Helsinki. A calling card tells about the scope of services that the studio offered: “The Decorative Art Office of Toini Kallio produces ryijys, flat woven carpets, designs for textiles. Designs and craft kits upon commission.” (Fig. 2). I was fascinated, because in the published sources there was very little about this artist and now I learned that she had an office! Printed tags with the name of her studio were also attached to fabric samples, thus implying organized marketing.

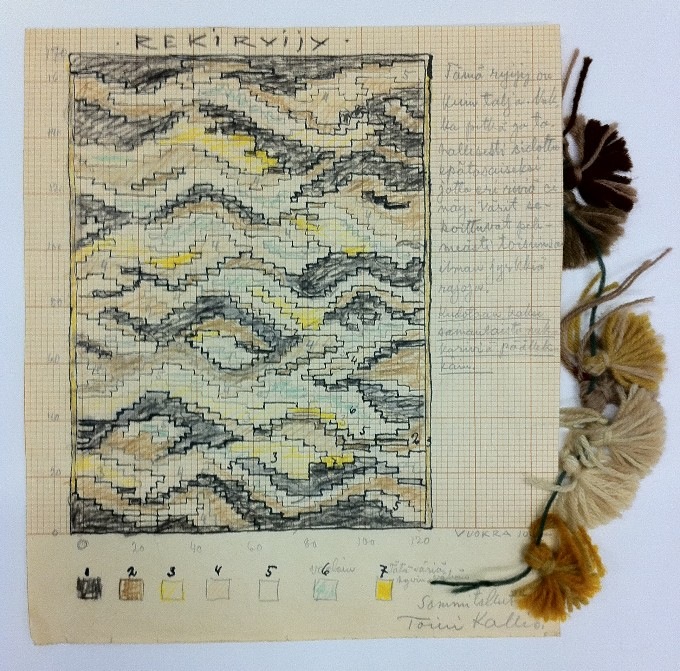

Apart from samples there are no textiles in the archive of Toini Kallio. Sometimes, however, a sketch or a pattern drawing contains essential information about the missing object. In this case, detailed instructions for the weaver, written by the artist on the side of a pattern drawing informs about the exceptional technique used in this particular textile. (Fig. 3). In the pattern drawings there is also evidence of operating directly with customers. Pencil markings tell, for example, how much it costs for the customer to borrow a certain design for a ryijy: ”Rent 150 marks for a three-month loan”. However, in this archive there are no other documents of the weaving studio. Even the basic information had to be gathered from other sources. Apart from a list of Kallio’s most important commissions, written presumably by the artist herself, all basic information on activities, production and the people involved are missing. A similar case is the archive of decorative artist Katri Warén-Waris (1891–1973, née Cannelin, also Warén), who had a private weaving studio and interior design firm in Turku.[15] Also in this archive, donated by the family, the ”design material”, pattern drawings, sketches and tags provide evidence of networks and activity. There is, however, no other information about the production.

3. Toini Kallio: Pattern drawing for a ryijy, 1930. ”This ryijy is like hide. The pile is long and it is deliberately knotted unevenly so that the rows will not show. The colours blend without strict borders. Two similar rows are woven one on the other.” Toini Kallio archive, Design Museum Helsinki. Photo: Leena Svinhufvud.

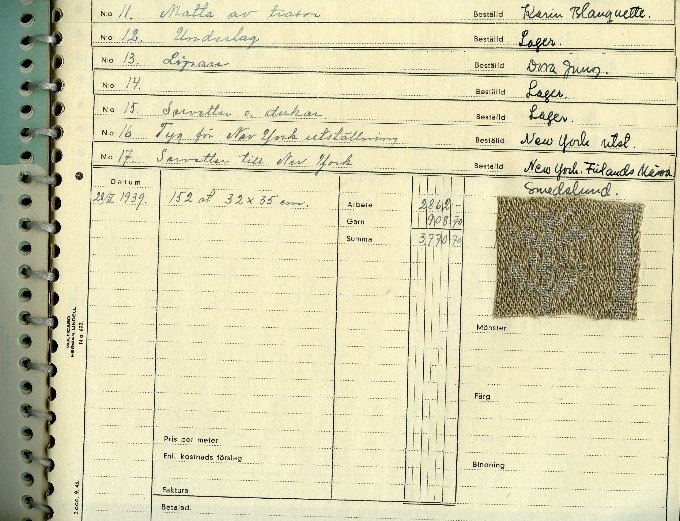

The archives of textile artists who are known to have had studios during the inter-war years do not generally contain information on economic matters. There are no ledgers, receipt books or price lists and even material on the products is sporadic and rare from this period. Without this kind of evidence how can one prove that a weaving studio or “decorative art office” even functioned? Luckily there was an exception. The workbooks of Dora Jung’s (1906–1980) weaving studio, active in Helsinki from 1932 until the death of the artist, give concrete information about the activities: the products, weavers and even the clientele. On the basis of this material, I could count the amount of textiles produced annually. For example during 1939 (the year when systematic documentation was started) the weaving studio produced over 100 metres of curtain fabrics and there were several private orders for woven tablecloths and napkins. There is a card for each project of the studio, often with a textile sample. Thus, I could also see what kinds of textiles were sent to the New York World’s Fair in the same year. (Fig. 4). The Design Museum received the large Dora Jung collection in early 1980s, immediately after the death of the artist, and further material was donated in 2008 by relatives. The extensive archive has been used in several exhibitions.[16] It contains a lot of material on individual commissions of ecclesiastical textiles and unique, one-off art pieces, which is also the work for which Dora Jung has been known until the present. However, detailed documents about the serial production of utility textiles in this archive open up a completely new perspective on the artist. They also demonstrate the capacity of a weaving studio basing on hand weaving.[17]

4. Card No. 17: “Napkins to New York”. A card from a workbook of Dora Jung’s weaving studio documents that 152 napkins of linen damask, shown in the sample, were hand woven for the New York World’s Fair of 1939. Dora Jung archive, Design Museum Helsinki. Photo: Leena Svinhufvud.

In the Finnish art and design scene of the inter-war period there were some twenty ‘weaveries’, ‘design offices’, ‘studios’ or similar enterprises run by artists such as Maija Kansanen, Toini Kallio and Dora Jung. Only a few of these studios were formally registered and many did not last very long. Entrepreneurship was not a contemporary notion but one that is widely used today to describe organizing and marketing production in the private sector. However, I argued that the work of women designers who organized the production of their own designs could be compared to women’s traditional entrepreneurship. Often based at home, and eschewing public records, the business of women selling food, clothes and care, tends to remain invisible in economic surveys despite the undisputed significance and considerable scale of this type of manufacture and commerce, as noted by the Finnish historian Kirsi Vainio-Korhonen.[18]

As economic actors, textile artists created new meanings for crafted textiles in the context of applied art and design. Eva Anttila (1894–1993), a central figure in Finnish textile art,[19] who also had for a while a private weaving studio, described her professional field as essentially connected to utilitarian aims and commercial practices. She stated that knowledge of colours, materials and a sense of style are the methods of the modern textile artist. Anttila wrote in 1933: ”Only a few years ago the prevailing idea was that applied art products are only for the wealthy, who in their glamorous homes have a suitably dignifying place for an artistic tankard or a painstakingly made wall-hanging. Today a modest young couple visits an applied arts workshop and equips their whole standard home of two rooms and a kitchen inexpensively and practically.”[20]

Eva Anttila’s testimony was essential when I formulated my argument about entrepreneurship in Finnish inter-war textile art. Her statement substantiates the fact that running a business was not regarded as antithetic to the identity of an artist. However, the artist-based archives in museums are more ambivalent sources because of the selection processes that precede the formation of a collection. Besides institutional control practised by the museum, also the value systems of the profession have a great impact on available sources. The crucial question is what kind of material is considered worth preserving by the donator. In the case of the painter Ester Helenius, who donated her sales records as part of her legacy to the Art Museum of Hämeenlinna, the Finnish art historian Tutta Palin has interpreted this as an indication of her pride in making a living from her art, as an independent woman.[21] It seems, though, that including documents of business activities – of selling one’s art – in the personal “museum collection” has been a sensitive issue for other artists.

According to my colleague, Ebba Brännback, who worked as the curator of collections at Design Museum Helsinki during the past three decades, material on concrete production and economic matters has seldom been offered to the museum. Finances and money have been considered a delicate issue; for example information about wages is commonly understood as confidential and subject to disposal.[22] This parallels my own experiences of interviewing textile artists. Sometimes they provide a very clear idea about what the textile artist considers relevant in his or her career and, respectively worth preserving. I have been told several times that the textile artist has thrown away everything that has to do with finances as it was considered unimportant and perhaps a bit risky, too. One textile artist who later worked solely with art objects wanted me to dismiss the part of her career that she in hindsight considered “commercial”. The commercial products of her weaving studio included, for example, woollen blankets and men’s ties, very popular items that were sold in a Helsinki department store and even exported. This was in the 1960s and her work was actually part of a much wider phenomenon. How should a researcher relate to this self-censorship that will erase a part of the history of textile art?

Discovering hand-woven serial production

In Design Museum Helsinki there is a large archive of textile designs of the Friends of Finnish Handicraft (Suomen Käsityön Ystävät, hereinafter also FFH). This Helsinki-based association was founded in 1879 to promote Finnish style and domestic crafts production. The association began to organize design competitions in the 1890s and from the turn of the century it worked extensively with Finnish artists, architects and designers to generate contemporary textile designs for Finnish homes. Still promoting itself first and foremost as ‘art organization’ the association was reorganized as a limited company in 1920.[23] The archive of original sketches consists of almost 7000 textile designs dating from a period of 100 years. Most of the designs have been obtained through public design competitions and thus, represent the jury-selected elite works of their time.[24] The hand of the artist is visible in individual sketches and examples from this archive have also been used in exhibitions to illuminate the style of a period. The well-preserved collection of authentic sketches by a number of Finnish artists was also the first archive that was digitized at the Design Museum in the early 1990s. I will return to the sketch archive later in this article.

The historical collection of the FFH was donated to different institutions with the support of the Finnish Ministry of Education and the acquisition was part of an operation to rescue the company, which was in economic difficulties. Thus it also reflects the values of the company and Finnish cultural policies of the period. The entire archive donation was organized by interior designer Lisa Johansson-Pape (1907–1989), long-term artistic director and former employee of the company. When organizing this big collection in the mid-1980s, Johansson-Pape capitalized on her thorough personal knowledge of the company.[25]

5. Laila Karttunen: Fabric sample Virta (Stream), cotton and rayon, 1930s. The Friends of Finnish Handicraft archive, Design Museum Helsinki. Photo: Design Museum / Rauno Träskelin.

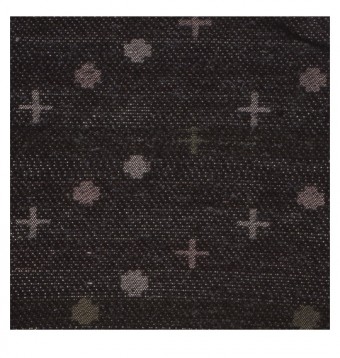

A collection of fabric samples came to Design Museum at the same time as the sketches. Compared with the sketch collection the samples were not systematically organized, many of them lack information about designer and date. Identified by Lisa Johansson-Pape there are files of samples designed by textile artists who headed the weaving studio and worked as in-house artists: for example Laila Karttunen (1895–1981), Lotta Ring (1915–1965) and later, Lea Eskola (1923–2012). In one of the boxes containing samples by Laila Karttunen there is the curtain fabric called Virta (Stream). According to a tag attached to the fabric, it was designed for a café or a salon. (Fig. 5). Some of the samples have detailed information, for example designer and product names, materials and descriptions of construction – but more rarely the date, though. However, most of the older samples, distinguished also by their quality and design, are without any information. In rare cases there is written information on a tag attached to the textile. Sometimes a price is indicated or the width of fabric. In fact, these random tags, which I dated to the 1920s and 1930s, aroused my interest in the crafted serial production of interior fabrics. Though not attributed or dated, the samples gave evidence of organized product development in this field.

Further information, however, had to be sought in documents kept in the National Archives of Finland. My research revealed that during the 1920s and 1930s the FFH systematically developed a line of woven interior fabrics.[26] Already in the annual exhibition of 1919 it presented a line of furniture fabrics designed by the contemporary head of the weaving studio, crafts teacher Valborg Madsén-Himanen (1888–1965). Ten years later the company’s weaving studio was headed for the first time by a trained textile artist, Laila Karttunen, who was especially recruited to renew the line of woven textiles. In the 1930s, production methods were rationalized using standard widths of fabrics and individual product names. The array of products was astonishingly wide: according to the 1938 inventory – one of the very few listings of production that is preserved – the company offered at least 75 types of furnishing fabrics and approximately 70 types of curtain fabrics, with some of the patterns woven in different colourings. There were larger commissions for interior fabrics for contemporary building projects, one of the most noteworthy of these being the new Parliament House, inaugurated in 1931.[27] The FFH had a shop in Helsinki and, based on shop inventories and photographs, I have suggested that fabrics were sold there directly to customers. Information on eventual private customers is, however, sporadic. There is so far little research on the clients of the Friends of Finnish Handicraft, but it can be suggested that the modern hand-woven fabrics were used in the new middle class urban homes of Helsinki, whereas most of the ryijy craft kits were sold to homes in the countryside.

6. Hulda Potila: Pallo (Ball) sample for a furnishing fabric, wool. First prize in the furnishing fabrics competition organized by the Friends of Finnish Handicraft in 1938. The Friends of Finnish Handicraft archive, Design Museum Helsinki. Photo: Design Museum / Rauno Träskelin.

My research pointed to a line of products of the FFH in the inter-war years, which has been overlooked in later accounts of the company. The research and interpretation of hand-woven fabric samples in the museum collection require specialized knowledge. Samples are also problematic as exhibition objects, which affects their use and visibility in historical narratives. Attribution – designer and date – is a key question, and most of the samples lack it. As mentioned earlier, Lisa Johansson-Pape has identified some of them, but these attributions raise further questions. Firstly, we do not know on what basis she did her attributions. Secondly, she left a great deal of samples without “labels” (at least the work of Valborg Madsén-Himanen) but, interestingly, identified those designed by professionally educated textile artists. This demonstrates the focus on professional designers, which in a way unites the history and contemporary practice of the FFH and the museum. The artist-centred agenda of the FFH greatly expanded during the inter-war years with the success of craft kits and the high status of textile art in Finnish cultural life. The artistic leadership of the company, demonstrated, for example, by design competitions with juries, implemented the power of the national designer organization, the Association of Decorative Artists Ornamo (present-day Finnish Association of Designers Ornamo), founded in 1911, and consisting of professionally educated designers.[28] Obviously, the community of Finnish designers was also a critical network for the national design museum. At Design Museum, the profession has been one of the key criteria in collecting, the designer’s membership in national designer organizations or a recognized status in the field.[29]

The identifiability of samples is also connected to the hierarchies of production in the FFH. While new designs for ryijys and other “piece-like” textiles – carpets, curtains, wall-hangings – were acquired from competitions and, thus, are visible in the sketch archive, fabrics by the yard were designed by in-house designers.[30] There is, however, an interesting exception to the rule. In the 1930s, two design competitions of hand-woven fabrics by the yard were organized, where instead of sketches, entries were requested as samples. The preserved entries (samples), which were anomalies in the competition practice, were found among the other fabric samples in the FFH archive. The first prize was given to the design Pallo (Ball) by textile artist Hulda Potila (1894–1968) who was the head teacher of textile art of the Central School of Arts and Crafts in Helsinki and a sound expert in weaving (fig. 6).[31] This new idea of evaluating textiles as samples and not as designs illustrates the value that was placed on the contemporary design of fabrics. However, as these two competitions remained the only ones using samples, the tradition of designing on paper was not interrupted. Fabrics by the yard were designed by in-house designers also in the future and thus remained a specialized field of design.

7. Katri Warén-Waris: A sketch for a woven fabric, ca. 1930s, watercolour on tissue paper. Katri Warén-Waris archive, Design Museum Helsinki. Photo: Design Museum / Rauno Träskelin.

There are samples of hand-woven fabrics in several archives of textile artists in the Design Museum. In the archive of Katri Warén-Waris there are also some fascinating sketches for fabrics. One of them is the chequered pattern sketched with watercolour and gouache on tissue paper, which is possibly for a curtain or furnishing fabric. (Fig. 7). While the FFH archive contains no sketches for fabric designs from this period, here we have proof that ”non-figurative” designs and even repeat patterns for simple weaves like this were designed on paper.

Having seen many samples of hand-woven fabrics from the inter-war period, I had thought that they had been designed ”hands-on”, using the methods learned in weaving tuition, based on the theory of weaving structure and practical experiments with yarn at the loom. Also, a sketch for a woven fabric goes against the idea of instrument-specific design, designing “hands-on” that marked a break from the tradition of pattern drawing. This idea has been perhaps most powerfully mediated through the publicity of weaving studio of Bauhaus.[32] Handicraft as a laboratory for industrial production became a modernist idiom, and the traditional hand-loom became a medium of “sketching for the machine”.[33] However, educated already in the 1910s, Katri Warén-Waris did not have training in textile techniques. Her tuition had aimed at skills in pattern drawing and the sketch can be understood against that background. In her weaving studio, she had experts in hand weaving to help with the practical work.[34] In that context the sketch can also be read as a means of communication between the artist and the weaver.

Art objects and textile art: the problematic ryijy

In Finnish art history, textile art has been studied through conventions of the discipline, focusing on pictoriality and selecting as research subjects textiles that reflect the visual arts.[35] However, a piece of textile art is not easily comparable to a unique art object. To illustrate problems of classification I will take ryijy textiles as an example. The ryijy (Sw. rya, also known as ryijy-rug) is mostly a knotted and piled textile woven from woollen yarn. The history of this type of textile is long and extensive, but at the beginning of the 20th century it was considered typically Finnish and a modern decorative textile was created from it, based on local history. The “renaissance” of the ryijy was part of the nation building process of the newly independent country. The publication of The Ryijy-rugs of Finland by the ethnologist U. T. Sirelius in 1924 launched a boom of collecting and reproducing old ryijy textiles.[36] Specialized textile artists embraced the “ryijy craze”, developing nuances of expression and creating new functions for the technique. At the same time, they renewed another old tradition, that of tapestries, taking also there distance from naturalism and orthodox craftsmanship.[37]

In the 1930s new ryijys, abstract in design, and reformist also technically, were exhibited in Finland and abroad. Given international publicity in the politically sensitive years before and during the Second World War, these Finnish textiles regenerated a nationalist discourse where individuality of expression and the artist’s personal touch were underlined.[38] This discourse of the ryijy as an art form, expressing material-romanticism, was highly influential for the development of this genre into one of signature products of Finnish Design during the post-war years. Although individual and original, the ryijy designs of the 1930s were, however, meant for serial production. In fact, the idea of unique or art ryijys (Finnish: taideryijy) often associated with this period is of later construction.[39]

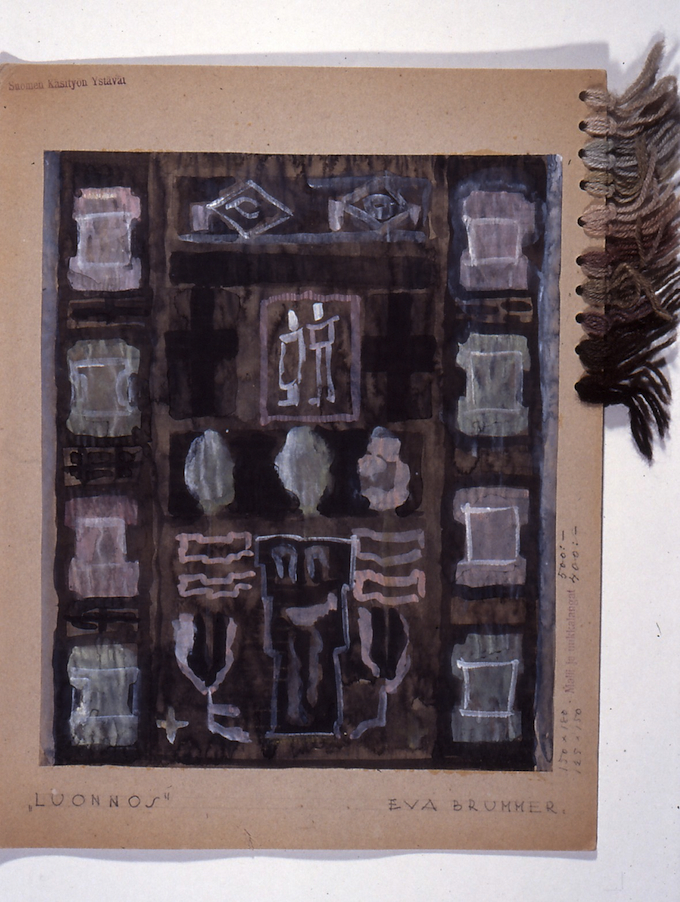

8. Eva Brummer: Luonnos (Sketch), undated sketch for a ryijy with yarn samples, watercolour on tissue paper. First prize in the ryijy design competition of the Friends of Finnish Handicraft in 1932. The Friends of Finnish Handicraft archive, Design Museum Helsinki. Photo: Design Museum / Rauno Träskelin.

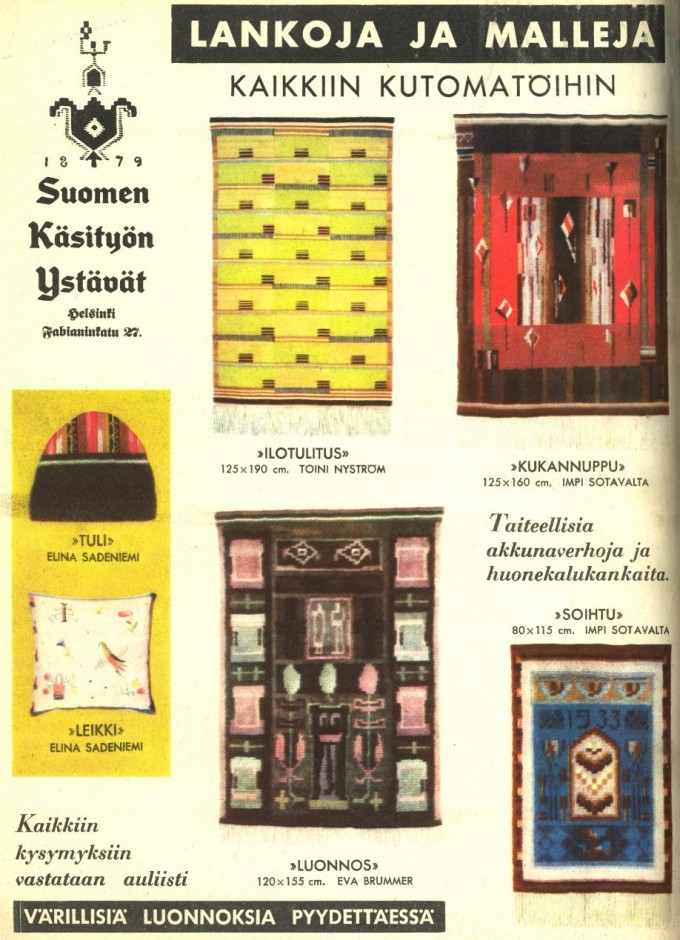

The Friends of Finnish Handicraft was a key actor promoting modern ryijys designed by artists. There are over 1300 ryijy designs in this collection. The FFH began to organize ryijy design competitions since 1904 and in the 1930s there were several competitions annually to meet the growing demand for patterns. One of the designs is called Luonnos (Sketch) by Eva Brummer, awarded in competition in 1932. (Fig. 8). The Luonnos ryijy was marketed for the readers of the popular Kotiliesi magazine in 1934 as a craft kit, a do-it-yourself ryijy for the Finnish home. (Fig. 9). The sales of craft kits were crucial for the economic growth of the FFH in the interwar period. The cultural historian Minna Koljonen has shown that craft kits for ryijy textiles were delivered throughout the country by mail order.[40] A new technique of sewing ryijys on a fabric was launched to overcome the challenge of using large hand-looms in urban apartments. When marketing these craft kits to Finnish consumers, the artistic value and individuality of the ryijy designs were underlined, and the name of the designer was always mentioned. So, at the same time when Luonnos by Eva Brummer was serially reproduced in the context of domestic craft, the “unique” artistic qualities of the ryijy were commoditized through marketing and exhibition critique.

9. ”Yarns and patterns for all weaving tasks. Sketches in colour on demand.” Advertisement of the Friends of Finnish Handicraft company to promote craft kits designed by Eva Brummer, Elina Sadeniemi, Toini Nyström and Impi Sotavalta. Published in Kotiliesi magazine in 1934.

Although we do not have the sales figures of this particular craft kit, there must have been several examples of the Luonnos ryijy in Finnish homes.[41] In the collections of Design Museum Helsinki there is also one “copy”. (Fig. 10). It is not documented when this ryijy was woven, but the Luonnos at Design Museum significantly resembles the version that was published in an advertisement in 1934.[42] However, when presenting this ryijy in exhibitions it is most often dated “1932” following the year of the sketch. In fact, the standard way to present ryijys, whether 20th-century designs by artists or reproductions of old folk ryijys, is with reference to the date of design or, in the case of the folk ryijys, the date woven in the textile.[43] This is, of course, correct, considering the creation of the design but a major mistake when dating the textile. The technique – which in itself is quite simple – has been reinterpreted according to later conceptions of the “original” technique and to changing ideals of the domestic environment, where these textiles were used. Also the materials have changed considerably from the wide variety of yarn types in the pile of 1930s ryijys. Standardization has been necessary in the serial production of craft kits, taking into consideration for example the quality and availability of yarn.

10. Eva Brummer: The Luonnos (Sketch) ryijy (DM G478), woven ca. 1933, wool and cotton (118 x 168 cm). Designed by Eva Brummer in 1932 for the Friends of Finnish Handicraft. The collections of Design Museum Helsinki. Photo: Design Museum / Rauno Träskelin.

Thus, there exist many kinds of objects based on a singular design idea: sketch(es), pattern drawings, and, finally, textiles. On the rare occasions when all the categories are available, the design process can be illustrated with these objects. However, the historical accuracy of this narrative should be questioned, as there were, in fact, several kinds of processes for reproducing ryijys from the original idea. The full process from sketch to textile took place at the FFH weaving studio where the first copies of new ryijys were woven by specialized craftspersons. The sketch by the artist (designer) was accepted for production by artist experts in a jury and by the board of the company. Then a pattern drawing based on the sketch was developed by the company’s trained draughtspersons, many of them textile artists by training. After the selection of yarns, the ryijy was the woven by a weaver.[44] The process aimed at the careful reproduction of the sketch. In the case of competition entries, the artist was later even expected to supervise the making of the piece. In practice, this included participation in the selection of yarns and following the progress of the weaving.[45]

From the 1950s onwards, close collaboration between the artist and the specialized ryijy weaver was publicly commended, and it became a trademark of the FFH. In some cases, a numbered series of limited copies was produced, implying the practice of reproducing art objects. The first copies were sometimes labelled with a tag on which both names were written and today these pieces are sought-after collectibles.[46] These “original” copies were often displayed in contemporary exhibitions and photographed, thus producing documentary material for historical research. Ryijys were, of course, also woven and sewn by amateurs with differing skills for their own homes, using for example the DIY-kits of the FFH. There were also so called “market ryijys”, illegal commercial reproductions of popular FFH designs that were produced semi-professionally in the countryside. The FFH had its own special materials and methods, which changed over the years but are nonetheless distinguishable and I think that it is possible to identify a ryijy woven by a professional weaver.

The production of contemporary textiles for Finnish homes was for a long while a key concept for the FFH. However, since the end of the 1970s the company has turned more and more to reproducing historical designs, one of the first being the Liekki (Flame) ryijy by the painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela dating from 1899. The number of historical designs in their catalogues has even grown over the past two decades.[47] Obviously, the continuous reproduction of designs over several decades challenges the researcher who has to indicate the place of an individual textile in this complexity. In the case of the ryijy, the authenticity of individual historical textiles is often considered secondary compared to “authentic” design. Commodification affected also the arts and craft practices and the “serial production” of ryijy art as craft kits can be studied in the context of changing meanings of art in the age of mass production.[48] We do not know, however, what the role of the artist/designer was for the contemporary consumer. The date of origin and the name of the designer, so important in a design museum context, are secondary information to people who owned a ryijy, as the survey of The Craft Museum of Finland shows.[49]

Concluding remarks

In the call for papers for the TAHITI4 conference the organizers asked whether material as such contains ‘truths’, or does our understanding of materials depend on our approaches and methods? I have described in this article how I reconstructed the work of modern textile artists based on information gathered from a variety of available sources. During the research process, I used information that I had absorbed when working in direct contact with the material. Samples of hand-woven fabrics were in this sense the most inspiring material. Textiles that so far had been without dating or attribution started to become meaningful.

I have argued here that the selection of sources and material guides our conception of textile art. Limiting the investigation to art objects in museum collections gives a different result than when searching for traces of entrepreneurship. Representing textile art of the inter-war period with wall-hangings such as those by Maija Kansanen (fig. 1) underlines the decorative (“artistic”) aspect of feminine craft. Moreover, exercised in the museum context the canon of the unique piece of art obscures the work of these women designers as heads of their own studios.

My art-historical research project is based on personal experience of a museum collection. I used material that was uncharacteristic of previous studies in textile art and access to all kinds of materials in the Design Museum collections was highly important for me. The heterogeneous and more or less sporadic archives of artists and designers were central for my study, containing new kinds of material and also representing the values and ideas of the artist. My most fruitful sources, ledgers and other economic documents and workbooks, however, are of questionable status in the art-museum system so far and I think that my work points to a gap in museum sources. Material of production and economic affairs were not previously thought relevant to be collected and made available as a resource for researchers either by the museum or the textile artists. Fortunately, the situation is changing and contextual historical information is considered more and more important also in this field. Finnish Industrial Design Archive in Mikkeli, the national institution devoted to documenting the history of design enterprises will hopefully in the future also contain material about textile artists’ businesses.

As a researcher my questions and motivation grew from contemporary challenges in museum work, acknowledging the importance of historiographical reflection and constant re-evaluation of the methods of writing history. Design objects have not lost their significance but quite the contrary. The aura of the object has not vanished and today, there is a whole array of symbolic key objects that the audience wants to see in an exhibition of Finnish design. It is mostly the visually interesting, undamaged and clean objects that tell the story also in museum exhibitions, not the samples and sketches.

Unlike many design historians and textile historians, I focused on the profession of educated textile artists. In the 21st century this outline may seem outdated as the work of educated designers provides a very narrow selection of material culture and as the line between professionals and those who are not is debatable. However, ”designer textiles” of the early 20th century make fascinating objects for art-historical research while crossing borders. They are produced both physically and discursively in the borderlines of tradition and the modern, handicraft and machine technology, high culture and popular culture. Even regarding the work of recognized artists and designers, it is still relevant to study the techniques and materials of their works. Also the questions of attribution and authorship (makership) are valid here – the processes of the collective that produces modern textile art.

Leena Svinhufvud is Curator of Education at Design Museum Helsinki since 1998. She holds a PhD in Art History from the University of Helsinki and has published widely on Finnish textile art and design. Her current research project focuses on hand weaving as medium for woman artists in the first half of the 20th century.

Notes

1. I wish to thank the referee for his or her constructive and thoughtful comments.

2. Svinhufvud, Leena 2009. Moderneja ryijyjä, metritavaraa, käsityötä. Tekstiilitaide ja nykyaikaistuva taideteollisuus Suomessa maailmansotien välisenä aikana. Helsinki: Designmuseo. [Modern ryijys, fabric by the yard and handicrafts. Finnish textile art and modernizing applied art during the inter-war years].

3. See also Wiberg, Marjo 1996. The Textile Designers and the Art of Design. On the Formation of a Profession in Finland. Helsinki: University of Art and Design.

4. An inspiring discussion about women’s strategies is in Kirkham, Pat & Walker, Lynne 2000. Diversity and Difference. In Women Designers in the USA, 1900-2000. Diversity and Difference. Ed. by Pat Kirkham. New York – New Haven & London: Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts and Yale University Press, 48-75.

5. Svinhufvud 2009; see also Svinhufvud, Leena 2011. Tekstiilitaiteilijat modernin kodin ihannetta toteuttamassa. In Sisustuskirja. Ed. by Jaana Kärnä-Behm. Kotitalous- ja käsityötieteiden laitoksen työpapereita. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto. [Textile Artists as Promoters of the Modern Home], 113-130.

6. Schoeser, Mary 2002. Introduction. In Disentangling Textiles. Techniques for the study of designed objects. Ed. by Mary Schoeser and Christine Boydell. London: Middlesex University Press.

7. I worked in the textile collections when I was still a student of art history. One of the projects was the re-organization of the sketches and drawings archive of the Friends of Finnish Handicraft (Suomen Käsityön Ystävät) in 1992 in conjunction with digitization. Later, I have curated some exhibitions based on the textile collections of Design Museum Helsinki, the latest being the exhibition Ryijy! The Finnish Ryijy-Rug! in 2009.

8. Ginzburg, Carlo 1989. Clues: Roots of an Evidential Paradigm in Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 96–125.

9. The date of weaving of this textile is not known and there is no definite document of acquisition for the museum collections. However, a wall-hanging (in Finnish “seinäkudos”) was bought from Maija Kansanen’s exhibition at The Museum of Applied Arts in 1929 for 3,500 Finnish marks. See the Annual Report of the Museum of Applied Art in 1929. The Archive of the Finnish Society of Arts and Design at the Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture, Helsinki; a photograph of this textile was published in 1935 with information that it belongs to the collections of the museum. Vävt och drejat. Finland. Nationalmusei utställningskataloger N:o 50. Maija Kansanen, Marianne Strengell, Kurt Ekholm. Text Nils Gustav Hahl. Helsinki: Frenckellska Tryckeriet AB, 1935; Cf. Aav, Marianne & Kalin, Kaj. Suomalainen muoto. Form Finland. Form Finnland. Taideteollisuusmuseon julkaisu 21. Helsinki: Taideteollisuusmuseo, 1986, 24.

10. Svinhufvud 2009, 61–66.

11. Svinhufvud 2009, 135–138; See also Tenkama, Pirkko 1987. Tavoitteena arkikauneus. Tekstiilitaiteilija Maija Kansanen, toimintaa ja tuotantoa. In Nainen – taide – historia. Taidehistorian esitutkimus 1985–1986. Ed. by Riitta Konttinen. Taidehistoriallisia tutkimuksia 10. Helsinki: Taidehistorian seura, 149–166. [The Objective of Everyday Beauty. Textile artist Maija Kansanen, her activity and production].

12. Hänninen, Kristiina 1988. Tekstiilialan taideteollisia yrityksiä Helsingissä vuosina 1900–1940. Tekstiilihistorian julkaisematon seminaariesitelmä. Helsinki: Tekstiilitaiteen laitos / Taideteollinen korkeakoulu. [Design enterprises in the textile field in Helsinki from 1900 to 1940].

13. See chapter Fabrics by the Yard, Svinhufvud 2009, 103–132.

14. When I researched the unprocessed archive in 2002, I found a small note indicating that the material was probably sent to the newly opened museum (1978) by a relative living in Helsinki; on Toini Kallio, see Svinhufvud 2009, 215.

15. Svinhufvud 2009, 213–214.

16. See the exhibition publications: Dora Jung. Ed. by Lisa Johansson-Pape. Taideteollisuusmuseon julkaisu No. 7. Helsinki: Taideteollisuusmuseo, 1983; Timonen, Pirkko 2007. Dora Jung. Tekstiilitaiteilija – taidekäsityöläinen – teollinen muotoilija. Tampereen museoiden julkaisuja 99. Tampere: Tampereen museot.

17. The potential of this material is used extensively by the educational researcher Päivi Fernström in her recent doctoral thesis on Dora Jung’s damask textiles. Fernström, Päivi 2012. Damastin traditio ja innovaatio. Tekstiilitaiteilija Dora Jungin toiminta ja damastien erityisyys. Kotitalous- ja käsityötieteiden laitoksen julkaisuja 31. Helsinki : Helsingin yliopisto, 2012. [The tradition and innovation of damask. The work of textile artist Dora Jung with a focus on her damask textiles].

18. Vainio-Korhonen, Kirsi 2002. Ruokaa, vaatteita, hoivaa. Naiset ja yrittäjyys paikallisena ja yleisenä ilmiönä 1700-luvulta nykypäivään. Historiallisia Tutkimuksia 213. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. [Food, clothes and care. Finnish female entrepreneurs from 1750 to the present day].

19. On Anttila see Salo-Mattila, Kirsti 1997. Picture Vs. Weave. Eva Anttila’s Tapestry Art in the Continuum of the Genre. Publications by the Department of Art History at the University of Helsinki No. 16. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

20. Anttila, Eva 1933. Uusia suuntaviivoja taidetekstiilissämme, Ornamon vuosikirja VI. Helsinki: Koristetaiteilijain Liitto Ornamo, 58–60. [New guidelines in our art textiles].

21. Palin, Tutta 2012. The Portrait as a Commodity in Early 20th Century Finland. In the session: Art and Economy – Art History and the Economization of Culture. NORDIK X Conference of Art History. Stockholm October 24th-27th, 2012.

22. Interview with Ebba Brännback, 28.9.2011, Helsinki.

23. On the history of the FFH, see Rakkaat Ystävät. Suomen Käsityön Ystävät 120 vuotta. Ed. by Päikki Priha. Helsinki: Ajatus, 1999. [Dear Friends. The Friends of Finnish Handicraft 120 years].

24. Svinhufvud, Leena 1999. Kuningasajatus – Suomen Käsityön Ystävien kilpailut. In Rakkaat Ystävät. Suomen Käsityön Ystävät 120 vuotta. Ed. by Päikki Priha. Helsinki: Ajatus, 70–85. [The competitions organised by the Friends of Finnish Handicrafts].

25. The material of FFH was divided between different archives and museums. Textiles and material relating directly to designers¬ – i.e. textiles, sketches and pattern drawings and samples – were placed in Design Museum while ethnographic and military-historical material was divided among other museums. Records and other documents went to the Finnish National Archives and some material from all these categories that were relevant to current production remained at the company. See Rakkaat ystävät 1999, 42, 136–139.

26. Svinhufvud, Leena 2012. Hand-woven fabrics by Yard. Unveiling modern industry of the interwar period. In Scandinavian design. Alternative histories. Ed. by Kjetil Fallan. London: Berg Publishers, 48–64.

27. Hakala-Zillicus, Liisa-Maria 2002. Suomen eduskuntatalo. Kokonaistaideteos, itsenäisyysmonumentti ja kansallisen sovinnon representaatio. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia 875. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 285. [Finland’s Eduskunta building. Gesamtkunstwerk, monument to independence and representation of national reconciliation].

28. See my discussion on power struggles in the inter-war arts and design scene in Svinhufvud 2009, 67–70; see also Svinhufvud, Leena 2012. Designers and textile production. In search of the meanings of the designer. In Boundless Design. Perspectives on Finnish Applied Arts. Ed. Paula Hohti. Helsinki: The Finnish Association of Designers Ornamo & Avain, 169-179.

29. Interview with Ebba Brännback, 28.9.2011, Helsinki.

30. On the “anonymity” of in-house designers, see Schoeser, Mary & Blausen, Whitney 2000. “Wellpaying self support”: women textile designers in the USA. In Women Designers in the USA, 1900-2000. Diversity and Difference. Ed. by Pat Kirkham. New York – New Haven & London: Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts and Yale University Press, 145-165.

31. Interestingly, her initials are embroidered on the back of the sample. In case they were there already in the time of the competition – as I presume – this identification contradicts the practice of competition in which the names of contestants were usually kept secret. On the competitions of FFH, see Svinhufvud 1999.

32. See for example the well-known texts by Anni Albers: Albers, Anni 1998 [1924]. Bauhausweberei. In Das Bauhaus webt. Die Textilwerkstatt am Bauhaus. Berlin: Bauhaus-Archiv, 100; and Albers, Anni 1979 [1938]. The Weaving Workshop. In Bauhaus 1919–1928. Ed. by Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius and Ise Gropius. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 141–145.

33. See for example Kaufmann, Edgar Jr. 1950. What is modern design? Introductory series to the modern arts 3. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 16.

34. Svinhufvud 2009, 213–214.

35. See for example the published doctoral thesis of Kirsti Salo-Mattila and Sinikka Peltovuori. Salo-Mattila 1997; Peltovuori, Sinikka 1995. Linnut liiteli sanoja. Laila Karttusen kuvatekstiilien problematiikkaa. Helsingin yliopiston taidehistorian laitoksen julkaisuja XIV. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto [Birds Flied Words. Problematics of the Pictorial Textile Art designed by Laila Karttunen]; Cf. Wiberg 1996.

36. Sirelius, U. T. 1926 (1924) The Ryijy-Rugs of Finland. A Historical Study. Helsinki: Otava; On the history of the ryijy as a Finnish phenomenon, see Ryijy! The Finnish Ryijy-Rug! 2009. Ed. by Leena Svinhufvud and Eeva Viljanen. Helsinki: Designmuseo.

37. See chapter The Ryijy as an Art Form in Svinhufvud 2009, 73–101.

38. Kalha, Harri 1999. Valööriryijy: valoa ja varjoja. In Rakkaat Ystävät. Suomen Käsityön Ystävät 120 vuotta. Ed. by Päikki Priha. Helsinki: Ajatus, 86–107; see also Kalha, Harri 1998. The Other Modernism. Finnish Design and National Identity. Finnish Modern Design. Utopian Ideals and Everyday Realities 1930-97. Ed. by Marianne Aav & Nina Stritzler-Levine. New Haven and London: Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts and Yale University Press, 29–52.

39. See discussion in Svinhufvud 2009, 92–96.

40. Koljonen, Minna 2003. Tekstiilitaidetta postipakettina. Suomen Käsityön Ystävien tarvikepakettien postimyynti 1925–1939. Unpublished master’s thesis in Cultural History, Faculty of Humanities, University of Turku. [Textile art in a post parcel. The mail order sales of crafts kits of the Friends of Finnish Handicraft 1925–1939]

41. See Koljonen 2003; On discussion of the ryijy in popular culture, see Ahonen-Kolu, Marjo – Manninen, Raija & Vesanto, Anne 2009. “The best pictures have a ryijy in the background”. A Close-Up View of the Ryijys of the Craft Museum of Finland. In Ryijy! The Finnish Ryijy-Rug! 2009. Ed. by Leena Svinhufvud and Eeva Viljanen. Helsinki: Designmuseo, 277–281.

42. According to the annual report, a ryijy designed by Eva Brummer and produced by The Friends of Finnish Handicraft was bought to the collections in 1933 for 1250 Finnish marks. The Annual Report of The Museum of Applied Art in 1933. The Archive of the Finnish Society of Arts and Design at The Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture, Helsinki.

43. On the complex issue of interpreting dates woven into folk ryijys, see Sihvo, Pirkko 2009. Rakas ryijy. Suomalaisten ryijyt. Helsinki: Suomen kansallismuseo. [Dear Ryijy-Rug. Ryijy-Rugs in Finland]

44. On the working practices in the FFH, see Svinhufvud 2009, 37–44, 143–144.

45. On the unique colour ryijy, see Polus, Minna 2009. Forest. A Great Example of Pointillism in the Art of Ryijy in Ryijy! The Finnish Ryijy-Rug! 2009. Ed. by Leena Svinhufvud and Eeva Viljanen. Helsinki: Designmuseo, 282–286.

46. On the collector’s perspective, see Sopanen, Tuomas & Willberg, Leena 2008. The Ryijy-rug lives on. Finnish Ryijy-Rugs 1778–2008. [Varkaus]: Varkauden taidemuseo, 2008.

47. Through receiving the archive collection of the FFH, the Design Museum Helsinki has become responsible for controlling the reproduction of historical designs based on material in the archives.

48. Jennings, Michael W. 2008. The Production, Reproduction and Reception of the Work of Art. In The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility, and other writings on media by Walter Benjamin. Ed. by Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty and Thomas Y. Levin. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 9–18 et passim.

49. See Ahonen-Kolu, Manninen & Vesanto 2009.