Abstract:

From its inaugural issue in 1873 to the end of the 19th century, the Milan-based illustrated weekly newspaper L’Illustrazione Italiana helped popularize Rome in its new role as the secular capital of modern Italy. This essay explores the implications of its news coverage as more than just documentation, but as implicit endorsement and promotion of the nationalization and secularization of the Eternal City. Following the completion of the Risorgimento, Italy’s reunification movement, one of the biggest challenges facing the newly united nation was overcoming strong regional diversity and a proud tradition of independent republics and small kingdoms. Rome was the only city which all regions could support as the national capital, a central and dominant position reflected in the publication’s masthead. L’Illustrazione Italiana was particularly important in disseminating images to a broad national audience of the architectural projects and ephemeral events in the new national capital relating to Vittorio Emanuele II, the king who oversaw reunification and who best personified the new Italian state. His usefulness as a human embodiment of nationalist values greatly increased with his unexpected death in 1878, not long after the leftist Sinistra party had seized control of parliament. Successive Sinistra leaders actively fashioned projects relating to the king as aggressively patriotic expressions of Italian state power. The pages of L’Illustrazione Italiana chronicled in detail the king’s funerals in the ancient Roman Pantheon, the various events and national pilgrimages to his tomb there, and the contentious restoration of the Pantheon that removed external signs of its ecclesiastical role as a church. No urban project in Rome enjoyed more attention than the lengthy genesis of the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, eventually erected on the north slope of the Capitoline. By the time its construction began in 1885, the king had been firmly established as the symbol of the new nation in the capital and his office – and by extension the Italian state – associated with the grandeur of ancient Rome in an effort to symbolize their permanence. Through its selective coverage, focusing disproportionately on projects relating to the king, and its often transparently patriotic text, L’Illustrazione Italiana can be seen as a participant in the shaping of history.

The article is written in English

Although not an official mouthpiece of the royal Italian government, the Milan-based L’Illustrazione Italiana helped popularize the Eternal City in its new role as the national capital of modern Italy. From its inaugural issue in 1873 (three years after Rome became the capital) to the end of the 19th century, this illustrated weekly newspaper regularly profiled Rome. One of the biggest challenges facing the newly united nation was overcoming strong regional diversity and a proud tradition of independent republics and small kingdoms. Rome was the only city that all regions could support as the national capital. For the Italian state, there was the additional challenge of counteracting the on-going presence of the pope.

L’Illustrazione Italiana was particularly important in disseminating images of the various architectural projects for the new national capital.[1] Central to the propagandizing project of remaking Rome in a new secular image were representations of Vittorio Emanuele II, the king who oversaw the Italian reunification movement and who best personified the new Italian state. His usefulness as a human embodiment of nationalist values greatly increased with his unexpected death in 1878, not long after the leftist Sinistra party took over parliament in 1876 and retained control for most of the next quarter century. All of the urban projects in Rome sponsored by the Sinistra government emphasized the theme of permanence, which reflected their political aspiration to possess Rome and played a major role in the definition of the king’s posthumous image. The pages of L’Illustrazione Italiana chronicled in detail the king’s funerals in the ancient Roman Pantheon, the various events and national pilgrimages to his tomb there, and the contentious restoration of the Pantheon that removed external signs of its ecclesiastical role as a church. No urban project in Rome enjoyed more attention than the lengthy genesis of the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, eventually erected on the north slope of the Capitoline.

While historians from a variety of disciplines (including urban and architectural history) frequently use representations from the pages of 19th-century illustrated weeklies to illustrate their analyses, the role played by those weeklies in shaping history is rarely considered. This essay examines how illustrated news coverage of patriotic events and urban interventions associated with King Vittorio Emanuele II and sponsored by the Italian government in the pages of L’Illustrazione Italiana helped solidify and popularize the transformation of Rome into the secular capital of modern Italy. Rather than analyze the government projects themselves, this essay considers the implications of their representation as more than just documentation, but as implicit endorsement and promotion by this northern Italian publication of the nationalization and secularization of Rome.

Popularizing the Centrality of Roma

L’Illustrazione Italiana was the leading illustrated weekly news magazine of its day in Italy, comparable to the earlier Illustrated London News (began 1842) and Harper’s Weekly in the United States (begun in 1857). Originally published with the name La Nuova Illustrazione Universale (changed in October 1875), “it spearheaded a drive by Fratelli Treves, one of the largest publishing houses in the country, to carve out a market across Italy for its products”.[2] Based on its high production quality, its relatively high newsstand price compared to other Italian news weeklies and the type of products and services advertised in its pages, John Dickie has deduced that its readership was mostly an urban bourgeoisie that spanned much of the country.[3] The regular politics of the country were rarely “a suitable subject matter for its own brand of celebratory patriotism. It preferred to deal with the paraphernalia of government, the ceremonies, personalities, and grand speeches. The many new patriotic monuments and rites of Umbertian Italy are perhaps the Illustrazione Italiana’s favorite of all topics”.[4] From the news magazine’s founding in 1873 until 1887, Emilio Treves directed its publication, while Raffaele Barbiera served as editor in chief from 1874 to 1904. They no doubt played a central role in editorial decisions and the degree of coverage of Rome and of the king. Among the artists working for the illustrated weekly, most images of Rome came from the hand of Dante Paolocci (1849-1926), who served as its correspondent there for three decades beginning in 1875. The sculptor Ettore Ximenes also supplied images to the weekly.

The Risorgimento, Italy’s national unification movement, drew its leadership and energy from the more prosperous and industrialized northern regions of the peninsula. The traditional seat of the Savoy dynasty and capital of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia since 1720, Turin became the first national capital of Italy, while its king, Vittorio Emanuele II, became the country’s first monarch. As the country quickly unified, the capital moved to Florence in 1865. Strong regional tensions, however, threatened the growing unification, which by then only lacked the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia and the Papal States based in Rome. Italian leaders, eager to see their country join the ranks of great European powers, had to overcome an acute sense of insecurity engendered by centuries of foreign domination, coupled with Italy’s late arrival at nationhood. They recognized that legitimacy as a country required Rome as the capital. Its capture on September 20, 1870, brought an end to the Risorgimento and opened a new chapter in the life of the Eternal City.

Fig. 1. L’Illustrazione Italiana masthead.

The masthead of L’Illustrazione Italiana (figure 1) clearly reflected the centrality of Rome within the cultural landscape of the newly unified Italy. Its architectural panorama evokes the masthead of the older Illustrated London News, which depicted the skyline of London. References to Rome dominate the centre of the composition, where a pedestal adorned with a relief carving of the She-Wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, the mythical founders of the city, supports an allegorical bust of Italy with the Star of Italy hovering above – a very popular symbol of the country during the Risorgimento. Flanking the pedestal in the foreground are a pair of allegories, to the left representing the arts, dominated by architecture, and to the right representing science and knowledge. An architectural panorama spreads out behind, centred on a frontal view of the Capitoline palaces, the seat of municipal power and symbol of Renaissance Rome, flanked by the ruins of the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum on the left and one of the city’s ancient triumphal columns to the right. To the left are representations of the Basilica di San Marco in Venice, the Two Towers in Bologna, and the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence; to the right are the Duomo in Milan and the Leaning Tower of Pisa and that city’s Duomo. The masthead also reflected the publication’s northern bias with no southern cities represented and only a smoking volcano in the far right distance, likely an allusion to either Mount Vesuvius or Mount Etna, to evoke the South. The masthead offered readers a weekly reminder of Rome as a secular national capital rather than as the capital of Catholicism and seat of the papacy. Conspicuously absent are any of the city’s churches or papal palaces. This focus on Rome paralleled the broader illustrated content of L’Illustrazione Italiana, which focused on the capital more often than other cities.

Defining the National Identify in the Capital

Although Pius IX’s capitulation to Italian troops on September 20, 1870, concluded the Risorgimento and ended 1500 years of papal temporal power, the royal government faced a unique political challenge in its new capital — the continued presence of a rival and still prestigious head of state in the Pope and the pervasive signs of Church power. His assertions of sovereignty threatened to undermine Italian claims to the possession of Rome and, worse, the legitimacy of the Italian state. A series of Destra governments, comprising coalitions of Catholic liberals, conservatives and clericals, controlled parliament from 1861 until 1876. They undertook an ambivalent occupation, attempting to avoid aggressive expressions of patriotism favoured by the opposition Sinistra, especially what they considered anachronistic identifications with antiquity that might antagonize the Pope and jeopardize a hoped-for peace accord. The situation for the Destra was complicated by the timing and nature of Vittorio Emanuele’s presence in Rome.

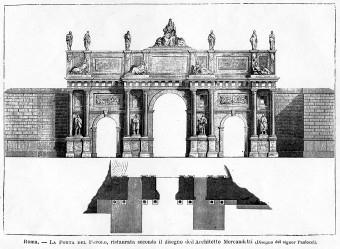

Fig. 2. Porta del Popolo, restored according to the design of architect Mercandetti. L’Illustrazione Italiana, Jan. 6, 1878: 5.

The dilemma of what image the king should portray in the new Italian capital was reflected in the debate over the manner of his first official entry. Alfonso Ferrero La Marmora, his Lieutenant in Rome counselled that “the King of Italy cannot … go to kneel down before the Pope; but much less can the King enter Rome as a conqueror treating the head of Catholicism with condescension”.[5] Such caution explains the relative paucity of representations of the king during the early years of Roma Capitale. Vittorio Emanuele used the occasion of the devastating flood of Rome in late December 1870 to make his first official, yet rather furtive visit to the city, arriving on the night of December 30 and appearing before the people of Rome from the balcony of the Palazzo Nuovo on the Capitoline the next day. Illustrations of his visit appeared in the undated publication Roma, la capitale d’Italia by Vittorio Bersezio.[6] Within the pages of L’Illustrazione Italiana, however, the king himself was most often depicted meeting with other heads of state or national heroes, such as German Emperor William I (in Milan) and Garibaldi (in Rome).[7]

The most conspicuous expressions of patriotism within the capital during the early 1870s were the annual celebrations of Constitution Day – the Festa dello Statuto – involving the unveiling of plaques on civic buildings, portrait busts of heroes of the Risorgimento in the Pincio park, and, beginning in 1872, pyrotechnic displays (girandole) launched either from Castel Sant’Angelo or from temporary constructions, which conformed to a long tradition in Rome of ephemeral monuments as a means of representation.[8] While such temporary constructions no doubt suited the cautious approach to nationalist imagery in the capital by the Destra-led Italian government, a concern for permanence was a central theme of the public works and monuments commissioned by the Sinistra during their decades-long hold on the national parliament beginning in 1876.

The “parliamentary revolution”[9] of March 1876 brought the anti-clerical Sinistra to power, a position of control it retained into the 20th century. L’Illustrazione Italiana initially labelled the change in government “The Crisis”, devoting three full unillustrated pages to the event in its March 26, 1876, issue, but on the covers of the subsequent weeks’ issues prominently profiled the new government ministers.[10]

To take possession of Rome properly, Sinistra leaders sought to mark the shift in power from papal capital to Italian national capital. Government-sponsored architecture and urbanism in the city thus had a two-fold purpose: it attempted to supplant papal imagery and destroy evidence of former Church control, and it consciously recalled the imperial iconography of ancient Rome to create an image of restored secular greatness. By recapturing the lustre of the golden age of Roman antiquity, they hoped to symbolize the promise of their fledgling Italy. An early expression of this secular patriotic agenda came not from the state, but from a project proposed in January 1878 by the Municipality of Rome for the transformation of the external facade of the Porta del Popolo, among the first architectural projects in Rome represented in the pages of L’Illustrazione Italiana (figure 2).[11] The renovation of the gate, designed by municipal architect Agostino Mercandetti, would have removed the papal insignia and dedicatory plaques from both sides. According to the account in L’Illustrazione Italiana, the new external facade would include statues in the intercolumniations “that would represent four of the men that worked and contributed most to the completion of Italian unity”. The author enthusiastically continues, noting that new bas-relief plaques would depict the story of “our Risorgimento, of which one should certainly be the entrance into Rome of Vittorio Emanuele”. Across the top, statues would represent the seven capital cities of the seven former states that constituted Italy, with Rome at the centre and the biggest. Although the external façade of the gate was expanded according to this design, the actual work retained all papal components and ignored the proposed patriotic imagery. The fate of this project, published just three days before the death of Vittorio Emanuele II, illustrated the challenge faced by the Sinistra in remaking Rome, given that the country’s Catholics generally remained sympathetic to the Pope.

The emergence of Vittorio Emanuele II as the central embodiment of the Italian state was distinct from the broader iconography of Italian patriotism, where he shared the limelight with other leaders of the Risorgimento – notably Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi. Alberto Mario Banti notes that the lives of these three main leaders of the Risorgimento were interpreted within the “national-patriotic cultural climate … idealistically as loyal collaborators, united in their effort to build the nation state. This was the orthodoxy imposed following the deaths of the three heroes, and it was the result of a careful political and cultural orchestration”.[12] While the pages of L’Illustrazione Italiana provided illustrated coverage of a wide range of patriotic events, it reflected a different reality, one that witnessed an unquestioned pre-eminence of King Vittorio Emanuele, with the magazine lavishing considerably more attention on the celebration of his memory than on any other subject.

For the ruling Sinistra, only the king possessed the appropriate political orientation to embody the constitutional monarchy of the Italian state, whereas both Mazzini and Garibaldi had advocated republicanism. As part of the long-lived House of Savoy, rulers of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia that became the de facto royal house of Italy, Vittorio Emanuele II stood out as the only figure capable of countering the international stature of the Pope. While in life Vittorio Emanuele preferred a non-confrontational presence in Rome, the king’s sudden death in Rome on January 9, 1878, gave the Sinistra government its first conspicuous opportunity to enhance the power of the royal image.[13] Over the following decade, a series of anti-clerical government leaders of the Sinistra, notably the successive Ministers of the Interior (Crispi, Zanardelli and Depretis) and the Ministers of Public Instruction (Coppino and Baccelli) sought to augment the national and imperial character of their king by equating the royal office with the ancient emperors of Rome. This practice had been used conspicuously by Napoleon earlier in the century both in terms of his own image and through architectural monuments erected in Paris. Napoleon’s embrace of imperial Roman imagery may have served as a model to the Italian leaders, who had the advantage of having Rome and its antiquities at their disposal with which to cement a connection between imperial Rome and modern Italy. Whereas Napoleon had expelled Pope Pius VI from the Papal States in 1799 as an assertion of his control over the Eternal City, the less powerful and tacitly diplomatic Italians instead used urban projects associated with Vittorio Emanuele II to showcase their authority in Rome and to signal the end of Papal temporal power.

The death of Vittorio Emanuele II in January 1878 also had a catalytic effect on the development of an urban renovation program by the Sinistra. The government had already announced its intention to involve the state in the urban affairs of the national capital, but, lacking a specific plan, had not yet acted. The two funerals held for the king (the second organized by the government itself) demonstrated the tremendous unifying power of the royal office and the enormous propaganda potential of its image. Meanwhile calls for a national monument to the king – what became known as the “Vittoriano” — provided Sinistra leaders with a popular mandate for direct urban intervention. The events associated with his funeral, annual commemorations of his death, his tomb in the Pantheon and the national monument to his memory erected on the Capitoline Hill brought regular illustrated attention to projects orchestrated by the Italian government within the pages of the popular illustrated weekly.

Aggrandizing the Image of the King at the Pantheon

L’Illustrazione Italiana provided detailed coverage of each stage in the ceremonies surrounding Vittorio Emanuele II’s death and funerals. For several weeks, its pages were filled with multiple images and detailed stories that reinforced his central position within Italian patriotic imagery. These included his lying in state in the Quirinal Palace and the funeral cortege that passed through several of the city’s most important piazzas and along its principal streets, with massive crowds, comprising people from all over Italy, lining the route, as in the Piazza del Popolo, which was documented with an impressive two-page illustration.[14] Most dramatic of all, however, were the two funerals held in the Pantheon.

The Pantheon had been chosen as the site of the royal tomb by Francesco Crispi, the Minister of the Interior and one of the most radical anticlerical members of the Sinistra government.[15] For patriotic reasons, politicians and popular sentiment agreed that Vittorio Emanuele should remain in Rome, rather than be returned to his native city of Turin, the traditional seat of the House of Savoy, for burial in the Superga, the family mausoleum. The choice of the Pantheon satisfied both the new king, Umberto I, who agreed to his father remaining in Rome on the condition that he be buried in a place of Catholic worship,[16] and the Vatican, which would allow his burial in “the church in Rome that is judged to be most convenient”, but excluded any of the Patriarchal Basilicas.[17] The Pantheon satisfied Crispi’s desire to augment the legitimacy and permanence of the nascent royal office, later declaring to parliament, “the throne [of Italy], like the state, must be firm and appear as such, [since] the stability of institutions is revealed to the people by the stability of [their] monuments”.[18] The desirability of the Pantheon for the royal tomb stemmed from a wealth of attributes beyond its merely being antique: it had had a venerable foundation under Augustus, by his First Consul, Agrippa; it boasted a good state of preservation, indeed the very best preserved among the city’s ancient landmarks; and, most importantly for an imperial mausoleum, it had a round shape, like the highly esteemed tombs of Augustus and Hadrian nearby.[19] No doubt they also had in mind the broader secular connotation of a “pantheon” as a place where a country celebrates and immortalizes its national heroes and great citizens, a tradition deriving from the Roman Pantheon but popularized during the French Revolution by the conversion and renaming of the Church of Ste. Geneviève into Le Panthéon for this purpose. The French use of the Parisian Pantheon to celebrate multiple heroes contrasted to the Sinistra leaders’ focus on Vittorio Emanuele II and their desire to align him alone with ancient emperors through the specific ancient associations of the Pantheon in Rome, a goal that kept them from burying any other Italian heroes there (apart from King Umberto I after his assassination in 1900).

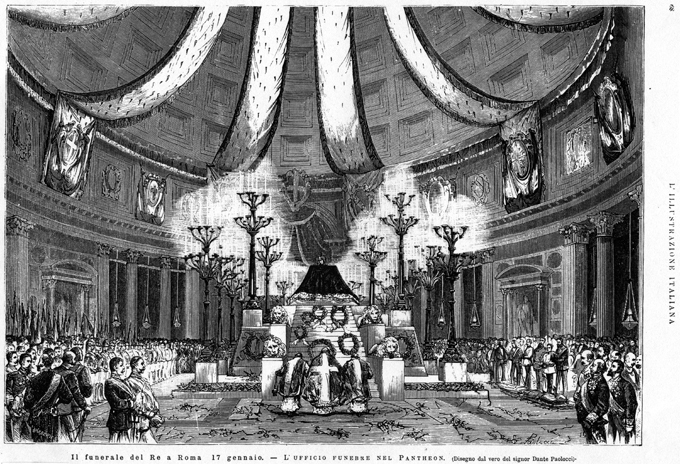

Fig. 3. View of the Official Funeral of Vittorio Emanuele II in the Pantheon showing the catafalque and temporary decorations, Jan. 17, 1878. L'Illustrazione Italiana, Feb. 3, 1878: 68.

The first “Official Funeral”, likely organized by the royal house, took place on January 17, 1876, and was ostensibly a religious service involving the solemn entombment of the king within a provisional resting place inside the Pantheon. The extravagant decorations – given a full-page illustration in L’Illustrazione Italiana – included a large catafalque containing the king’s body, adorned by no less than twelve candelabras supporting myriad candles and guarded by statues of eight imperial lions (figure 3). Overhead, long strips of velvet, draped from the oculus and secured at the base of dome, formed an enormous canopy. As the illustrated weekly reported, the widespread sympathy and patriotism

for the monarchy in our country was almost like a revelation. Not only the upper classes, but the middle and lowest classes were moved with such spontaneity and vivacity, from one end of the peninsula to the other, that the natural event became a political event, showing the solidity of the unity of the Italian monarchy. The patriotism won over the republicans and the clericals, save a few and isolated exceptions.[20]

The use of the word “revelation” was important, reflecting the sudden and impressive augmentation of Vittorio Emanuele’s reputation — in death. For the first time, the king became unquestionably the most potent symbol of Italian unity and therefore also of the state. The account also reflects the overtly patriotic tone of L’Illustrazione Italiana, whose editors clearly asserted a sympathetic stance towards the modern Italian state.

Interior Minister Crispi orchestrated the much more elaborate and decidedly secular second funeral, or state exequies, held on February 16, delayed by the need to prepare suitable decorations. Responsibility for the temporary decorations belonged to Michele Coppino, the Minister of Public Instruction, due to his control of national heritage; he appointed Luigi Rosso to lead a team of professors from the Royal Institute of Fine Arts in Rome to create the artistic program.[21] Their decorations, described in detail in L’Illustrazione Italiana, utterly transformed the Pantheon with suitably august and imperialistic adornments that fully exploited the burgeoning emblematic power of the king and his office.[22]

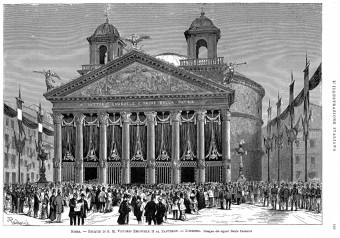

Fig. 4. Exterior of the Pantheon decorated by Luigi Rosso et al. for the state exequies of Vittorio Emanuele II, Feb. 16, 1878. L'Illustrazione Italiana, Mar. 3, 1878: 149.

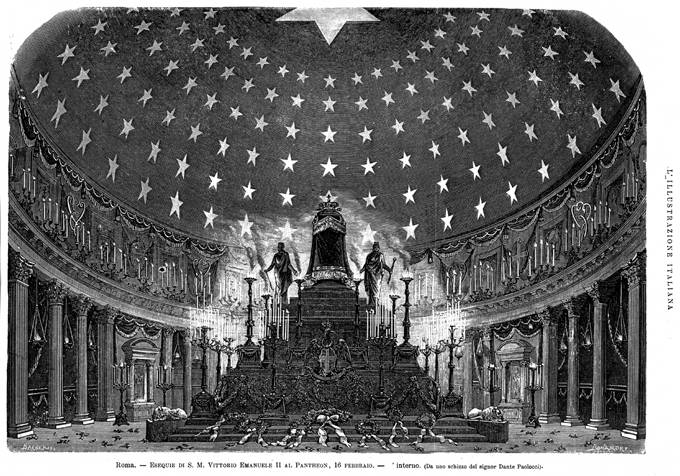

On the exterior, their work effectively “restored” the temple to its ancient state, resembling contemporary reconstructions of the building’s original appearance (figure 4). The decorations took full advantage of the symbolic associations of the Pantheon with fame and immortality, as well as its resemblance to ancient dynastic mausoleums. The acroteria above the pediment included at the peak an imperial eagle above some trophies, flanked by restored antefixae and, at the ends, allegories of Fame. Beyond these generalized symbols of authority, their decorative program attempted to augment the prestige of the Italian royal office by equating the Savoy dynasty with the imperial dynasties of antiquity. To this end, the tympanum scene represented the apotheosis of the House of Savoy. Covering the traces of the Agrippan dedication, meanwhile, the architrave inscription strengthened the identification of Italy’s first king with the first emperor of Rome: “Padre della Patria” was a direct translation of “Pater Patriae”, the epithet of Augustus. It was likely the first time Vittorio Emanuele II was so called and would become his most famous epithet. The equally fantastic interior decorations devised by Rosso’s team continued the dynastic iconography and utterly disguised the ecclesiastical purpose of the building (figure 5). Once again, an enormous catafalque occupied the centre of the space. Representing the king’s imperial power, reposing lions anchored the corners and a Savoy eagle filled the centre of each side. Covering the oculus overhead, the enormous Star of Italy took up its place at the centre of 140 gas-lit stars of the universe filling the coffers of the dome.[23]

Fig. 5. Interior of the Pantheon decorated by Luigi Rosso et al. for the state exequies of Vittorio Emanuele II, Feb. 16, 1878. L'Illustrazione Italiana, Mar. 3, 1878: 148.

Annual commemorations of Vittorio Emanuele II’s death continued the highly propagandistic aggrandizement of the royal office. Receiving detailed and illustrated press coverage in the pages of L’Illustrazone Italiana, these commemorations reminded readers – and anyone who experienced the events in person – of the imperial stature of the Italian royal house and of the state. The impressive temporary catafalque erected at the centre of the Pantheon on the occasion of the first anniversary would be reused in the commemorations of 1880 through 1882, further perpetuating the memory of the king. Designed by architect Giuseppe Massuero in the form of a tall baldachin, the structure featured imperial eagles and numerous smoking tripods that reinforced the king’s association with ancient emperors. The lone Christian reference appeared in the crucifix held by the figure at the summit. The predominantly secular character of these commemorations was noted in 1881 by Alessandro Guiccioli, a member of the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house in the Italian parliament), who recorded in his diary that “the official personages showed off their irreligiosity; all this chills and annoys; it was a civil celebration and not religious”.[24]

The “restoration” effected by the temporary decorations for the second funeral conformed to a widespread desire to restore the Pantheon to its ancient state, at the expense of its ecclesiastical character. As part of the country’s ancient patrimony, the national government, and specifically the Ministry of Public Instruction, had control over the exterior and all structural parts of the building, while the Church retained possession of the interior. [25] The entombment of the king in the Pantheon gave Italian leaders an opportunity to take at least partial control of this notable church interior, tipping the building’s ancient-ecclesiastical balance in favor of the former.

As soon as the government decided in April 1881 to keep the royal tomb permanently in the Pantheon, the Minister of Public Instruction Guido Baccelli (whose appointment five months earlier garnered prominent front-page coverage in L’Illustrazione Italiana, which noted that he was the first Roman in the government) led a campaign to restore the building’s exterior to its presumed “original” state.[26] Although a medical doctor by training, Baccelli was a leading enthusiast for antiquity in the ruling Sinistra and one of its most radical anti-clericals. He advocated removing all of the supposedly valueless post-antique Christian additions to the Pantheon in order to reveal its distinctive mausoleum-like rotunda. Besides scientific and aesthetic reasons for the isolation, Baccelli informed the Italian parliament that he also had political motives: revealing its round shape would stress the new function of the building as an imperial mausoleum.[27]

The isolation of the Pantheon sought by Baccelli conformed to a broader practice of disconnecting antiquities from the present urban fabric that had been encouraged since the early 19th century. The French restoration theorist Louis-Michel Rigaud de l’Isle had advocated a “theory of the two cities”, which demanded that ancient monuments be materially liberated from the living urban tissue down to the ancient soil and had first been applied to the Column of Trajan in a project designed by Valadier but carried out in 1810-1814 after the departure of the French.[28] The physical isolation of the Pantheon carried out by his Ministry of Public Instruction also illustrated an affinity for the ideals of Camillo Boito, Italy’s leading restoration theorist in the second half of the 19th century and a member of numerous government building committees in Rome, who condoned the removal of accretions that distorted the legibility of a structure.[29]

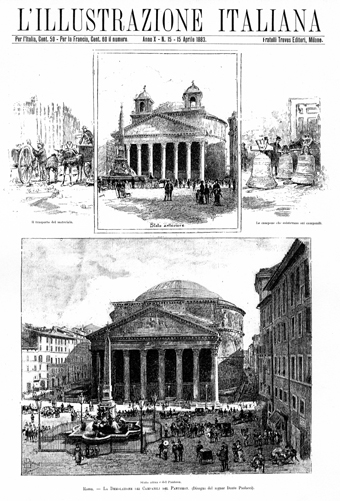

Fig. 6. Before and after views of the demolition of the Baroque bell towers on the Pantheon, April 1883. L'Illustrazione Italiana, Apr. 15, 1883: 233.

In May 1881, Baccelli received official authorization to expropriate the 17th-century Palazzo Bianchi, one of the buildings attached to the rear of the Pantheon, despite opposition from the state treasury, which had objected to the enormous cost – £415,000.[30] Baccelli’s ambition to uncover the exterior of the Pantheon in its entirety had to be abandoned when the demolition of the Palazzo Bianchi between July 1881 and March 1882 revealed the attached but deteriorated remains of what were identified at the time, as reported in L’Illustrazione Italiana,[31] as the Baths of Agrippa, which were conserved with only minor restoration work to ensure their stability. In April 1883 the Minister of Public Instruction further diminished the ecclesiastical appearance of the building by demolishing the two bell towers commissioned by Pope Urban VIII in 1626. L’Illustrazione Italiana provided front-page coverage of the effort (figure 6) and revealed their pro-government sympathy in reporting “As soon as the work of restoring the Pantheon began, l’Illustrazione hastened to publish a view of the work undertaken”.[32]

The progressive mythologizing of Vittorio Emanuele’s reputation to symbolize Italian unity intensified during the annual commemorations of the king’s death in 1883 and 1884. Accompanying a full-page illustration, L’Illustrazione Italiana commented how “The Pantheon, at Rome, has become the temple of the fatherland, since welcoming the mortal remains of the great Liberator King … the immortal Sovereign”.[33] The fifth anniversary observance in 1883 diverged from previous years by including a national pilgrimage. Besides paying homage to the king in the Pantheon, where wreaths were deposited, pilgrims also visited the Capitoline Hill, where the king had first addressed the city in 1870. L’Illustrazione Italiana noticed the enhanced character of that year’s commemorations, reporting “the veneration for the death of Vittorio Emanuele does not diminish with the passage of years, it increases”.[34]

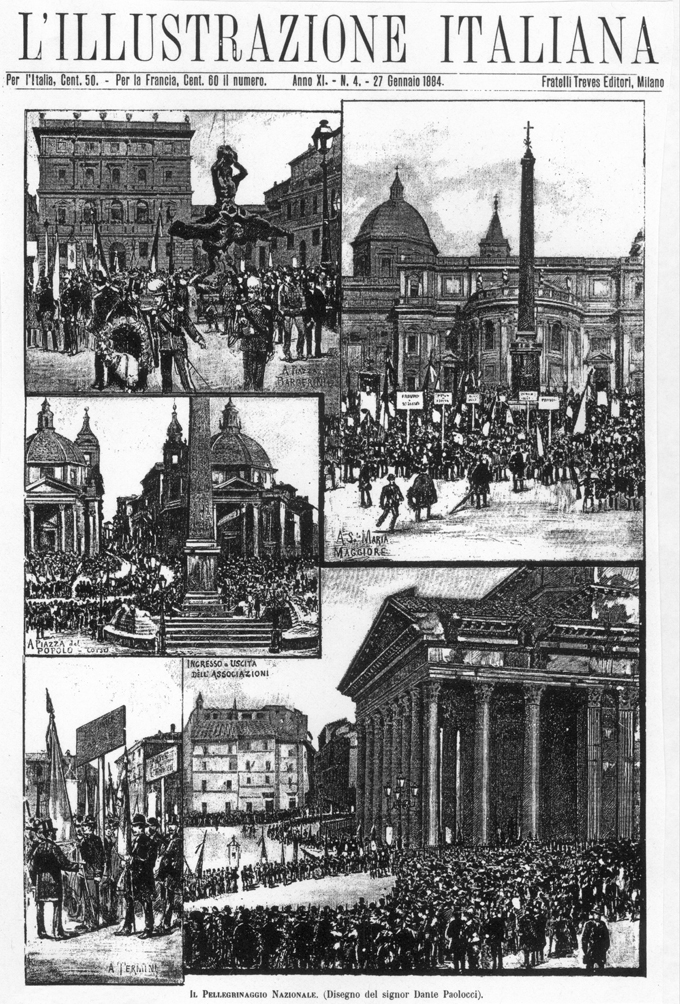

Fig. 7. Views of the National Pilgrimage to the Tomb of Vittorio Emanuele II, Jan. 9, 1884, seen clockwise from upper left in the Piazza Barberini, behind S. Maria Maggiore, at the Pantheon, at Termini train station and in the Piazza del Popolo. L'Illustrazione Italiana, Jan. 27, 1884: 53.

Within a few months of this event, private organizations around Italy began planning an even grander national pilgrimage to the royal tomb for January 1884.[35] The event had the objective of affirming the “Unity of the Fatherland” by honouring its founder, Vittorio Emanuele, together with the “four makers” of national unity — King Carlo Alberto (Vittorio Emanuele’s father), Count Camillo Benso di Cavour (Italy’s first prime minister), Mazzini and Garibaldi.[36] Predictably, the government took over control of the event and removed the homages to the other four in order to avoid weakening the centrality of Vittorio Emanuele.[37] The national pilgrimage attracted a large number of participants: 68,635 pilgrims, almost half of whom belonged to 2,061 patriotic associations, as well as 666 representatives from Italian colonies abroad.[38] L’Illustrazione Italiana devoted considerable attention to the weeklong event and emblazoned its January 27, 1884, cover with a montage of illustrations testifying to the enormous attendance (figure 7).

For the occasion of the 1884 national pilgrimage to Vittorio Emanuele’s tomb, Minister of Public Instruction Baccelli commissioned Giulio Monteverde to erect a “simulacrum” of his design for the royal tomb at the centre of the Pantheon.[39] Monteverde rejected the baldachin form of Massuero’s catafalque, perhaps to avoid its ecclesiastical associations. Instead, his construction involved a massive ancient-style sarcophagus rising eight meters above a broad ten-meter-wide base anchored at the corners by imperial lions.[40] On January 13, 1884, L’Illustrazione Italiana confidently reported that the “new tomb … will contain the venerated body of King Vittorio” and would require four years for construction.[41] The central tomb idea, however, was promptly scuttled by a combination of Vatican protests, aesthetic and structural concerns of the Fine Arts Commission and Prime Minister Depretis’s lack of enthusiasm for Baccelli and preference for a national monument to the king on the Capitoline Hill.

Towards a National Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II

Less than two years after taking over parliament, the Sinistra government was presented with the ideal opportunity to make a grandiose urban statement that declared their control of Rome. The death of King Vittorio Emanuele II in 1878 immediately prompted calls for the erection of a national monument in the capital. Just as quickly controversy erupted over what kind of memorial would best honour the monarch and the country. A protracted debate and two international competitions led to the final design, selected in 1884. L’Illustrazione Italiana provided extensive coverage of this process, illustrating the finalist designs and select others from each competition. Although realized after a quarter century of construction, the Vittoriano, as the monument came to be known, served from the outset of its development as the most powerful weapon in the propaganda arsenal of the Sinistra.

Prior to the first competition, the two-year debate over the monument helped the government to define its objectives – to erect a civil monument, not a religious sepulchre, a monument focused on the king, not a pantheon of illustrious Italians, and a monument of enormous size and national importance, not a mere statue. In terms of its secularity, its authoritarian subject and its scale, therefore, the monument had already acquired its most fundamental attributes. What form it should take remained unclear. As with the state exequies and pilgrimages, all attention as far as the government was concerned had to focus on the king as the embodiment of state power in Rome.

Formulating a design for the national monument to Vittorio Emanuele posed several formidable challenges to competitors. Besides allowing them complete artistic freedom, the program offered little direction, apart from demanding a monument to “the memory of” the king. They had to address all of the problems the government had avoided resolving: what location in Rome was most appropriate for the memorial? What form should it take and how large should it be? Which style should it have and how would it relate to the question of a national architecture? How should one depict the king iconographically and what values should the monarchy represent? What role should be assigned to the monarchy in Rome? And how to symbolize national unity and the Risorgimento?

The first competition, which left the location and monumental form up to the designers, attracted 315 submissions from thirteen countries by the September 23, 1881, deadline, of which 293 were accepted. According to L’Illustrazione Italiana, “many were mediocre, some fair, and very few worthy of serious consideration”.[42] On the surface, the entries offered a remarkable diversity of ideas for the monument. In his published summaries of the competition, architecture critic Piero Quaglia categorized the designs into six main groups: 1, triumphal arches; 2, honorary columns and monoliths; 3, temples; 4, statuary and isolated monuments; 5, bridges and building projects; and 6, monumental complexes.[43] The royal commission judging the competition comprised seven artists (one painter, two sculptors and four architects drawn from a broad range of academic institutions from across the country), seven politicians, with the Prime Minister serving as president of the commission, the Mayor of Rome and the president of the Accademia di San Luca. A week after commencing the judging on February 15, 1882, and over a month before issuing their decision on April 1, the commission had already determined that no project merited being built.[44]

In assessing the various entries, the commission gave the most attention to the designs involving monumental complexes, which received the top two prizes and characterized ten of the fourteen semi-finalists. The first place award was given to Henri-Paul Nenot, a young French architect and Prix de Rome winner studying in the city, who focused his project on the Piazza dell’Esedra on the edge of the modern city near the Termini train station. In her study of the Vittoriano, Catherine Brice argues that royal commission president Prime Minister Depretis influenced the award of the first prize to Nenot, either in an attempt to improve economic ties with France or to neutralize the potential domestic political problem of Italian regionalism, of appearing to favour one part of the country at the expense of all others.[45] Strong nationalist sentiment, however, prevented the public from sharing Depretis’s enthusiasm for Nenot’s design, which was accused of being too French.[46]

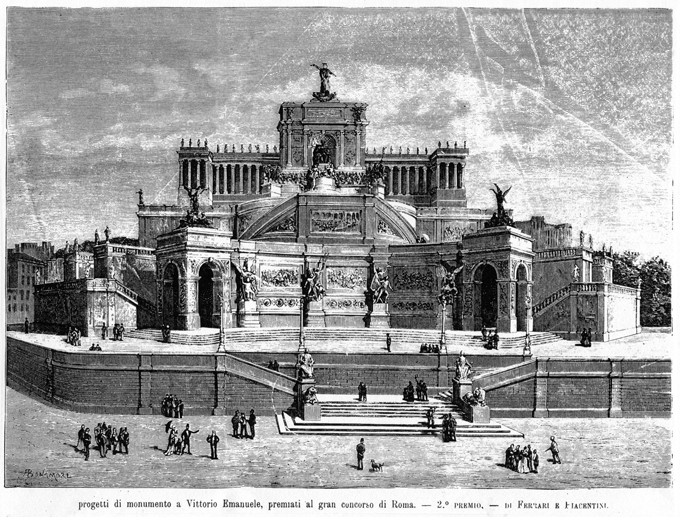

Fig. 8. Project for the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, first competition, 1882, by Ettore Ferrari and Pio Piacentini. L’Illustrazione Italiana, May 7, 1882: 328.

Although most attention had focused on Nenot, the most important and influential project in the first competition, however, was the second-prize entry by Ettore Ferrari and Pio Piacentini (figure 8). In contrast to the fruitless controversy over the details of Nenot’s design, the concept of a multi-tiered monument climbing the north slope of the Capitoline Hill and facing the Piazza Venezia had a profound effect on the commission. As commission member Alessandro Guiccioli wrote in his diary, “beautiful idea, mediocre execution”.[47] Indeed, it radically altered the evolution of the Vittoriano, eventually purging the commission of its fascination with the Piazza dell’Esedra and the associated symbolism of a monument in the new Rome. The full significance of the Capitoline site chosen by Ferrari and Piacentini came to the fore in the spirited and protracted site debate in the ensuing months.

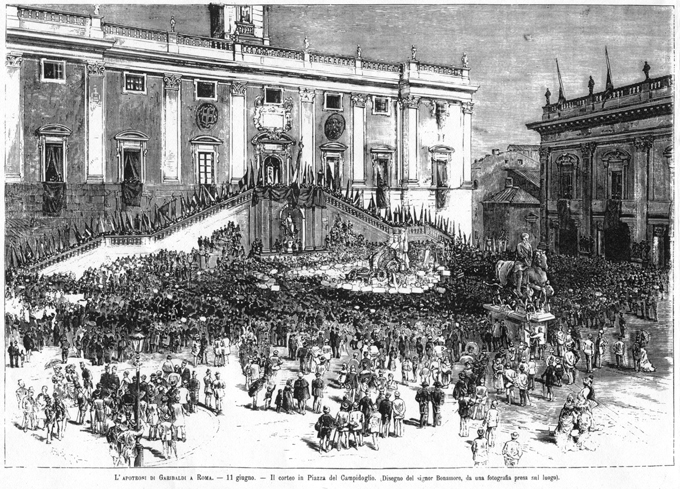

The death of Giuseppe Garibaldi on June 2, 1882, posed an immediate challenge to the king’s iconographic hegemony and evidently served as a catalyst in the development of the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele. The following day, the government approved funding for a national monument to Garibaldi,[48] though its budget of £1,500,000 was one sixth of that allocated for the Vittoriano, reflecting the king’s far greater political significance for the state. Further, when two members of parliament proposed that Garibaldi be entombed in the Pantheon the government promptly suspended the sitting.[49] The full extent of the challenge became evident on June 11, when a variety of anti-clerical, masonic, military and municipal groups commemorated the general’s death with an “apotheosis”,[50] evidently without government participation. L’Illustrazione Italiana reported how they constructed a float that employed the same neo-antique repertory of details that had been used to decorate the funeral catafalques for the king and how a large crowd of representatives from all the major cities of Italy “paraded to the Capitoline, where the spectators crowded one on top of the other as if awaiting the arrival of a Caesar, brought in triumph by way of the Sacra Via” (figure 9).[51]

Fig. 9. "Apotheosis" float and cortege for Garibaldi in the Piazza del Campidoglio, Jun. 11, 1882. L'Illustrazione Italiana, Jun. 25, 1882: 444.

The timing of Garibaldi’s death and the subsequent patriotic display in his honour at the Capitoline evidently had a decisive influence on the government’s efforts to commemorate Vittorio Emanuele. Four years and one unsuccessful international competition had already passed without any tangible progress on the national monument to the king. During the previous two months, the royal commission for the Vittoriano had met only once. Beginning on June 5, just three days after Garibaldi’s death, they held seven meetings over an eight-day period to debate the site of the structure. [52] Prior to the “apotheosis” procession to the Capitoline, the commission dismissed that hill as a potential site for the monument due to the high costs of expropriations and foundations and of establishing access routes; they even deemed the Capitoline inferior to the Piazza dell’Esedra for “artistic reasons”.[53] The popular celebration of Garibaldi at the Capitoline galvanized Prime Minister Depretis’s determination to see that celebrated ancient hill become the site of the king’s monument. The next meeting of the royal commission that he attended, on September 16, 1882, marked a decisive turning point: criticism of the Capitoline site was suddenly and otherwise inexplicably translated into support and the commission’s official selection of the Capitoline site.[54]

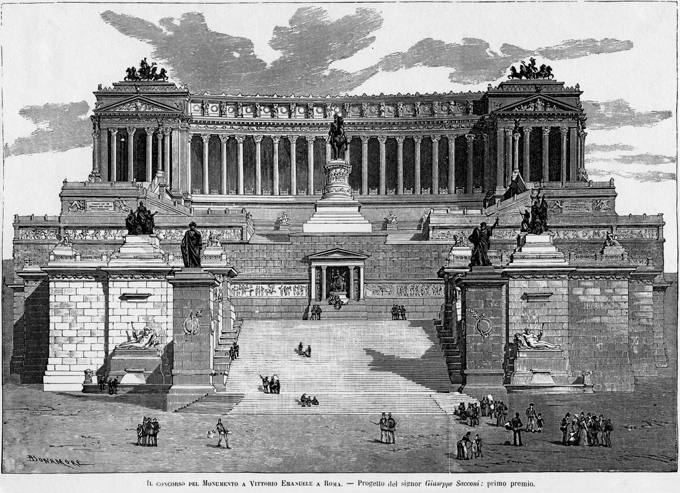

The second international competition for the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele, issued in December 1882 with a deadline of December 15, 1883, had a very clear program that grew out of the royal commission’s site debate. The monument had to comprise the following essential features: a) a bronze equestrian statue of the king to be placed on the main level and aligned with the axis of the Via del Corso; b) an architectonic backdrop in the form of a portico, a loggia or any other architectonic parti that hid the posterior buildings; and c) stairs ascending to the main level of the monument, which should lie 27 meters above the Piazza Venezia. This competition attracted 98 entries, of which three were selected by the royal commission on February 9, 1884, to be resubmitted in a third run-off competition. Along the way L’Illustrazione Italiana offered detailed coverage, illustrating representative entries in its February 24, 1884, issue including that of Giuseppe Sacconi, one of the three finalists invited to develop his design further and the eventual architect of the monument (figure 10). On the occasion of the placing of the first stone, Sacconi designed an elaborate temporary amphitheatre on the site, along with a central pavilion. L’Illustrazione Italiana provided a detailed account of the event accompanied by four illustrations, optimistically concluding “It is undoubted that this work will be the most important artistic work of our unification and that among the monuments of the first and of the second Rome, it will underscore to posterity the value of the third Rome, of the Italian Rome”.[55]

Fig. 10. Project for the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, second competition, 1883, by Giuseppe Sacconi. L'Illustrazione Italiana, Feb. 24, 1884: 125.

By the time work began on the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II in 1885, the king’s symbolic and iconographic primacy had been firmly established – a position aided by the unrivalled attention he received in the pages of L’Illustrazione Italiana. Commemorations of the other heroes of the Risorgimento paled in comparison: Garibaldi’s monument, a large equestrian statue on a tall pedestal, was erected on the summit of the Janiculum Hill, far from the centre of Rome; and the Mazzini Monument would not be completed until 1895 and was a very modest statue in a small piazza beside the new Corso Vittorio Emanuele. The enormous scale, central location and protracted construction of the Vittoriano ensured the continued attention of the Italian people up until its completion in 1911.

Conclusion

Through its profiling of selective national government-funded urban interventions in Rome during the 1870s and especially the 1880s, L’Illustrazione Italiana helped popularize the city’s new identity as the national capital of Italy. The editorial preference of the news weekly for focusing on architectural projects and ceremonial events associated with King Vittorio Emanuele II, particularly after his death in January 1878, reflected the enormous popularity of the monarch and his status as the de facto public face of the government. By contrast, other government projects enjoyed significantly less, if any, attention in the pages of L’Illustrazione Italiana, such as the creation of the Via Cavour and the Corso Vittorio Emanuele in the heart of the historic centre, the erection of the massive river walls, or the colossal Palazzo di Giustizia. By examining L’Illustrazione Italiana in the context of Rome’s transformation in the late 19th century, this essay considers illustrated weeklies not just as a convenient (and copyright free) source of visuals of historic events or works for historians, but as a participant in the shaping of history.

Robin B. Williams chairs the Architectural History department at the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD). He specializes in the history of the built environment of the modern period in Europe and North America. Williams earned his B.A. in the History of Art at the University of Toronto and his M.A. and Ph.D. in the History of Art at the University of Pennsylvania, with his dissertation examining the transformation of Rome into the capital of modern Italy during the late 19th century. Since joining SCAD in 1993, Williams has made Savannah the principal focus of his research. From 1997 to 2006, he directed the online Virtual Historic Savannah Project <vsav.scad.edu>. His recent publications have addressed issues relating to the commemoration of Native Americans and the role of historic street pavement in modernizing American cities. He is the lead author of a new architectural guidebook, Buildings of Savannah (University of Virginia Press, 2016).

[1] This article draws on material from my Ph.D. dissertation: Williams, Robin Brentwood 1993. Rome as State Image: The Architecture and Urbanism of the Royal Italian Government, 1870-1900, University of Pennsylvania. Accessible online through ProQuest, http://dissexpress.umi.com/dxweb/search.html. The author wishes to thank his doctoral advisor, David Brownlee, for his longstanding encouragement and support. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewer who made several excellent recommendations that strengthened this essay.

[2] Dickie, John 1999. “The Power of the Picturesque: Representations of the South in the pages of Illustrazione Italiana,” Chapter 3 in Darkest Italy: The Nation and Stereotypes of the Mezzogiorno, 1860-1900. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 83.

[3] Dickie 1999, 83 and 85.

[4] Dickie 1999, 87.

[5] Quoted in Chabod. Politica estera Italiana, 216, n.2. See also Brice, Catherine 1997., p.289.

[6] It is not clear if these illustrations had previously appeared in the news press. See Bersezio, Vittorio c.1872. Roma, la capitale d’Italia [publisher and date of publication not identified], 475-484. The text of this section, entitled “Roma libera,” was from an earlier publication: De Amicis, Edmondo 1872. Ricordi del 1870-71. Florence: Barbera.

[7] See L’Illustrazione Italiana, Oct. 24, 1875, and Feb. 14, 1875.

[8] Syrjämaa, Taina 2006. Constructing Unity, Living in Diversity: A Roman Decade. Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters, 138-141 and 180-183. For a detailed study of the Festa dello Statuto and its role in shaping Italian nationalism, see Porciani, Ilaria 1997. La festa della nazione. Rappresentazione dello Stato e spazi sociali nell’Italia unita. Bologna: Il Mulino.

[9] For a discussion of this event, see Fonzi, Fausto 1972. “Tentativi di Conciliazione (1871‑1900)”. In Roma Capitale. Roma: Istituto di Studi Romani Editore, 143. See also, “Settimana Politica: La crisi” L’Illustrazione Italiana Mar. 26, 1876: 338–339, 342.

[10] See “Settimana Politica: La crisi” L’Illustrazione Italiana, Mar. 26, 1876: 338–339, 342. For the profiles of the government ministers, see L’Illustrazione Italiana, Apr. 2, 1876: 353–354; Apr. 9, 1876: 369–371; and Apr. 16, 1876: 385–386.

[11] “La Porta del Popolo a Roma” L’Illustrazione Italiana, Jan. 6, 1878: 4–5, 11.

[12] Banti, Alberto Mario 2012. The Remembrance of Heroes. In The Risorgimento Revisited: Nationalism and Culture in Nineteenth-Century Italy. Ed. Silvana Patriarca & Lucy Riall. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 171.

[13] Catherine Brice has explored the issue of the king’s image through the published eulogies. See Brice, Catherine 1997. “La mort du roi: les traces d’une pédagogie nationale,” In Mélanges de l’Ecole française de Rome. Italie et Méditerranée, vol. 109, no. 1, 288.

[14] See L’Illustrazione Italiana, Feb. 3, 1878: 72–73.

[15] For a detailed analysis of the significance of Pantheon in this period, see Williams, Robin B. 2015. A Nineteenth-Century Monument for the State. In The Pantheon: From Antiquity to the Present. Ed. Tod A. Marder & Mark Wilson Jones. Cambridge University Press, 356–379.

[16] Letter, Anzino to Depretis, Feb. 14, 1883, ACS, Min.Int, GabAD, Ser.1849–95, b.8, f.9.

[17] Letter, Anzino to Depretis, Jan. 11, 1878, ACS, Depretis, Ser.1, b.23, f.83.

[18] Crispi, speeches of Mar. 10 and 17, 1881. In Atti Parlamentari, Camera, Discussioni, 4250 and 4457.

[19] At least one contemporary observer made the explicit connection between Vittorio Emanuele’s tomb in the Pantheon and the imperial mausoleums: see Lattari, Francesco 1879. I monumenti dei principi di avoia in Roma. Roma: Tipografi Elzeviriana nel Ministero delle Finanze, 330.

[20] “Rivista Politica,” L’Illustrazione Italiana, Jan. 27, 1878: 50.

[21] Magni, Basilio 1878. Descrizione dell’apparato fatto nel Pantheon. Rome, 5 n.1.

[22] “L’esequie per Vittorio Emanuele nel Pantheon,” L’Illustrazione Italiana, Mar. 3, 1878: 139.

[23] Magni, Apparato nel Pantheon, 13-14.

[24] Guiccioli, Alessandro 1936 (1881). “Diario del 1881″ Nuova Antologia 71:1544, Jul. 16, 1936: 184.

[25] Williams, A Nineteenth-Century Monument for the State. 364-365. On the cultural jurisdiction of the Ministry of Public Instruction, see Williams, Robin B. 1992. “An Unsung Protagonist of Roma Capitale: The Ministry of Public Instruction and Its Documents at the Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Rome.” In Annali Accademici Canadesi, vol. 8, 97-105.

[26] “Il Ministro Baccelli,” L’Illustrazione Italiana, Jan. 16, 1881: 33.

[27] Baccelli, text of speech, entitled “Onorevoli Colleghi!,” undated [ca. Dec. 1881], Archivio Centrale dello Stato (ACS), Direzone Generale di Antichità e Belle Arti (DGABA), Versamento (vers) 1, busta (b.) 120, fascicolo (f.) 172, sotto-fascicolo (s.f.) 37. Subsequent references to documents from this archive will use the short forms within the parentheses.

[28] Pinon, Pierre 1985. “Roma antica,” in Forma: la città antica e il suo avvenire, ed. A. Capodiferro, Roma: De Luca, 21-23.

[29] Boito, Camillo 1989. Il nuovo e l’antico in architettura, ed. Maria Antonietta Crippa, Milan: Jaca Book, 107-126.

[30] Decreto [contratto], Baccelli, Ministro della Pubblica Istruzione, Nov. 9, 1881, ACS, DGABA, Vers.1, b.119, f.172, sf.37.

[31] “I restauri del Pantheon,” L’Illustrazione Italiana, Apr. 15, 1883: 234. The remains are now identified as the Basilica of Neptune.

[32] “I restauri del Pantheon” 1883: 234.

[33] “Il nove gennaio al Pantheon,” L’Illustrazione Italiana, Feb. 4, 1883: 71.

[34]. “Il nove gennaio al Pantheon” 1883: 71.

[35] For an exhaustive analysis of the organization and significance of the national pilgrimage of 1884, see Tobia, Bruno 1991. Una patria per gli italiani. Rome/Bari: Laterza, 100–142.

[36] Tobia 1991, 111.

[37] Tobia 1991, 113 & 137–138.

[38] Tobia 1991, 136.

[39] Letter, Depretis to Baccelli, Jan. 29, 1884, ACS, DGABA, Vers.1, b.123, f.174, sf.5.

[40] “Il Pellegrinaggio nazionale,” L’Illustrazione Italiana, Jan. 13, 1884: 22.

[41] “Il Pellegrinaggio nazionale” 1884: 22.

[42] “L’Esposizione de’ Bozzetti,” L’Illustrazione Italiana, Feb. 5, 1882: 99.

[43] Quaglia, Piero 1882. Quattro Chiacchiere intorno ai progetti pel Monumento da erigersi in Roma a Vittorio Emanuele. Roma: Tipografia Elzeviriana, 3.

[44] Commissione Reale per il Monumento a Vittorio Emanuele II, Verbale 19, Feb. 23, 1882, ACS, Ministero dei Lavori Pubblici, Direzione Generale, Edilizia, Divisione 5, b.45, f.122.

[45] Brice, Catherine 1986. L’Immaginario della terza Roma I Concorsi per il Monumento a Vittorio Emanuele II a Roma. In Il Vittoriano: Materiali per una storia. Ed. Pier Luigi Porzio. Rome: Fratelli Palombi Editori, I:20.

[46] Quaglia 1882, 32.

[47] Guiccioli, Alessandro 1936 (1882), “Diario del 1882″ Nuova Antologia 71: 1546, Apr. 1, 1882, 436.

[48] Guicciolo 1936 (1881), 443.

[49] Guicciolo 1936 (1881), 443.

[50] “L’Apoteosi di Garibaldi,” L’Illustrazione Italiana, Jun. 25, 1882: 446.

[51] “L’Apoteosi di Garibaldi” 1882: 446.

[52] See the minutes of the Royal Commission. Comm. Reale Mon.a Vittorio Emanuele, ACS, Ministero dei Lavori Pubblici, Direzione Generale, Edilizia, Divisione 5, b.45, f.122.

[53] Comm. Reale Mon. a Vittorio Emanuele, Verbale 19.

[54] Comm. Reale Mon. a Vittorio Emanuele, Verbale 19.The three-month delay had been caused by the Prime Minister’s obligations to parliament during the summer session. See AP, Camera, Discussioni, Jun. 15, 1882: 11661.

[55] “La Prima Pietra al Monument di Vittorio Emanuele,” L’Illusrazione Italiana, Apr. 5, 1885: 218.